The first week of January arrived with brittle sun and a courthouse that smelled like paper and disinfectant. Sable met me on the steps in a charcoal coat, hair pinned like a scalpel. “Breathe,” she said, which was the closest she ever got to tenderness. Inside, we sat on a hard bench beneath a bulletin board full of lost mittens and notices about road closures. The clerk called our case with the thin bell of a service counter. I stood when Sable stood.

The judge was a woman with winter in her eyes and a wedding band worn thin with time. She glanced over our file—photos, stills, the video of Dad at the mailbox, the locksmith’s invoice we’d subpoenaed from his company—and then at me. “Ms. Stewart,” she said, “your evidence is exceptionally organized.” I didn’t mean to, but I glanced at Sable; she allowed herself a microscopic nod.

Dad tried to speak from the gallery, the old theatrical baritone. The judge cut him off with a single raised finger. “Sir, you are represented. Your counsel will address the court, not you.” His lawyer—the blazer man from my porch, stripped of the word ‘mediator’—rose with a speech about family misunderstanding and the burdens of pregnancy. Sable didn’t object. She simply let him use up his oxygen. Then she stood and pressed play on silence: our screenshots barked through the room one after another—Mom’s “non‑negotiable,” Dad’s “be useful,” Julian’s boxes, the administrative filings, the forged tenancy agreement with the fictional middle initial, the DMV attempt, the utility calls, the Facebook “miracle,” the 2:11 a.m. delivery to Box 42.

The judge asked only three questions. To me: “Did you ever invite them?” No. “Did you ever consent?” No. “Do you own this residence personally?” “It’s owned by Hian Pine LLC, Your Honor. I am the managing member.”

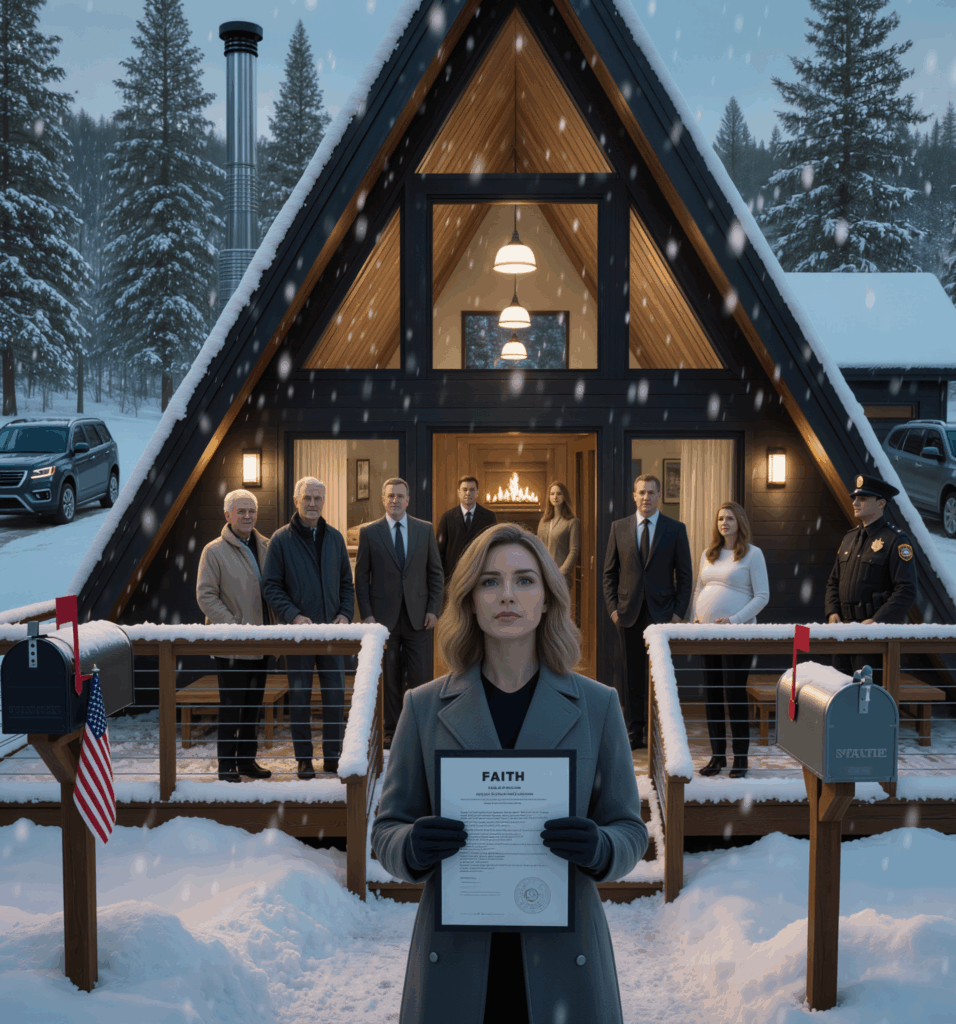

The order issued like weather. Full protective order granted. No contact outside counsel. No entry onto the parcel, road easement, or mailbox cluster. No filings purporting to act on behalf of the property. Any violation: immediate arrest and contempt. The gavel didn’t bang. It didn’t need to. The paper with her signature weighed as much as a door.

In the hallway, Mr. Harrison approached with the courteous smile of a man who had learned nothing. “Ms. Stewart, if we can have a word about restoring communication—” Sable stepped between us like a drawbridge. “Future communication goes to my office.” She handed him a card, cool as slate. “Also, a professional note: when acting as a mediator, do not step into advocacy. You’ve muddied your credibility.” He flushed—just once—and turned away.

On the drive back to High Timber, the sky performed that clear‑after‑storm blue I’d seen in magazines, unscarred and absurd. I pulled into Grocer’s on Main and bought coffee and something decadent from the bakery case, because celebration needs sugar even when celebration looks like paperwork. The cashier—her name tag read KAREN with glitter stickers around it—leaned in like we were old conspirators. “Saw your porch lights on New Year’s,” she said. “Sounded like you had a full house.”

“I did,” I said. “Thank you for the cinnamon rolls.” She winked. “Sarah told me to send you more next time the road ices.” In a town where everyone scrolls, information moves like snowmelt: quiet, inevitable, nourishing when you’re thirsty.

Back at the A‑frame, I placed the court order behind glass in the same frame as my guest policy, not as threat but as boundary art. Priya texted a photograph from her apartment: a hand‑lettered sign she’d made, joking, “NO TENANTS BY ANNEXATION,” taped to her own door. Luz sent a link to a fund for the county library’s winter program with a note: “Your fortress inspires public goods.” Gabe edited a spreadsheet into a checklist for anyone in our friend group buying property: deed structure, password hygiene, camera angles, mail protocols—the practical liturgy of autonomy. He titled it Quiet_Is_A_Choice.xlsx and shared it with a little lock icon. I cried in the way people cry when their nervous system realizes nothing is on fire.

Belle wrote three days later from a separate number. “I understand if you block me,” she began, and I read every word anyway. She described the engine of expectation she’d married into and the way my house became the symbol of a future she was told to believe in. “I said no on your porch,” she wrote. “I’m saying it again in writing. I will not be used as the reason for someone else’s theft. If you need a statement, I’ll give it.” I thanked her and didn’t ask for anything more. She texted a picture of a sonogram, a little comma of potential floating in the gray. Against my will, something in me warmed; not forgiveness for the others, but a different heat—like the fireplace when you’ve just added a log: future warmth, not yet visible, already certain.

Nana sent me her wedding silver. It arrived wrapped in old tissue that smelled faintly of cedar chest and winter perfume. The note said, “For your own holidays. Use daily. Tradition used correctly is just memory with manners.” I polished the forks until my reflection ghosted long and thin in them and then served myself scrambled eggs on a Tuesday with a fork that had witnessed three generations make bad decisions and keep eating anyway.

By mid‑January, the mountain shifted from postcard to place. A storm dropped snow like a soft verdict; a week later a warm wind came barreling through the pass and turned the driveway into crushed glass. I learned to scatter sand from a bucket I stored by the steps. I learned the exact minute the east side of the deck unfroze in the morning and where the shadow from the peak kept a trick strip of ice no matter what the sun insisted. I learned to listen to the heating system the way I used to listen to conference rooms—every hum meant something, every clank had motive.

On a Saturday, I found a wooden box in the loft closet. Not a trope, not a letter from a past owner—just a neat collection of screws, a labeled bag of spare cabinet hinges, two packets of stain, and an index card with measurements written in engineer’s print for shelves that would fit the odd slant under the eaves. I built those shelves because the world leaves you blueprints sometimes if you open every door. The smell of sawdust rose like a remembered story; when I slid the last board in, it seated with a small, satisfying click. I stacked the shelves with books I loved and with the heavy folder labeled Deck_Boundaries, placed not as paranoia but as liturgy: a record of what it costs to make a life.

Sable called with updates like a metronome. “The DMV added a fraud lock to your parcel.” Click. “The postmaster flagged their names; any forward generates a manual review.” Click. “The utility company added a voiceprint; your cadence is the key.” Click. “Your father’s counsel withdrew.” Click. “No new filings.” Silence like music.

In late January, Dad emailed my work address again. The subject line this time: “Reconciliation Framework.” Inside: a document that looked like something from a management seminar—swim lanes, stakeholder maps, bullet points about phases. Phase I: Acknowledgement. Phase II: Temporary Co‑Habitation. Phase III: Intergenerational Asset Optimization. I read it with the clinical curiosity of someone studying an insect under glass. I forwarded it to Sable with a single line: “For the archive.” Then I created an email filter that shunted future messages like that into an unlit basement where they could multiply without stinging anyone.

Mom tried a different vector: a handwritten card with an illustration of a snowman in a hat. The note said she missed me, that she wanted to start over, that she could bring ham up some weekend when the roads were clear. It didn’t mention the locksmith, the forgery, the mailbox. I placed her card inside the Deck_Boundaries folder, a specimen properly labeled in the case.

The town threaded me into itself one errand at a time. Sarah taught me the trick to the post office line (arrive during the 1:10 p.m. lull when the lunch rush thins). Tom showed me how to wrap a hose bib with a rag and a bungee cord before the deep freeze. The clerk at Hardware On The Pass learned my name and the size of the screws I bought without looking. “Three‑inch exterior wood,” he said one morning, holding out the box before I spoke. “For when you want things to stay put.”

One afternoon I found a bird stunned on the deck—brown, small, heartbeat a frantic drum. I cupped it in my gloved hands until its eyes cleared and it launched itself back into the air with a sound like a thank you that didn’t require words. It was the gentlest lesson the house gave me: you don’t save anything by convincing it to stay. You warm it in your safe, open palms and let go.

Work demanded a trip east. I didn’t want to leave the mountain, but independence isn’t a synonym for isolation; it’s a platform for choices. I set the cameras to alert the sheriff’s desk directly if any of the barred plates approached the ridge road and drove to the airport with less fear than I carried through entire Decembers of my childhood. In the hotel’s bland cheer, I drafted a talk for the Tideline board about authenticity as a brand strategy and laughed at my own hypocrisy because nothing I believed about authenticity came from work. It came from a door I had locked myself and the set of keys I wore in my pocket like jewelry.

On the flight back, a woman in the next seat asked about the photo on my phone background—deck, fog, the first winter sunrise I’d captured like a proof. I told her I’d moved to the mountains alone. She said, “Weren’t you scared?” I said, “Yes. And then I learned I could be scared and safe at the same time.” Her eyes went wet. “I’m sixty,” she said. “I think I’ll start now.” I wanted to press my extra house key into her palm by reflex, but boundaries are love, too, so I wrote the name of a bookshop on a napkin instead and told her to start with warm socks and a deadbolt that throws like a promise.

February arrived like a sharpening stone. The protective order became a piece of furniture in my house—present, unremarkable, effective. Once, my phone pinged with a plate read that matched Julian’s old SUV. It turned out to be a tourist with one digit different; the relief that melted me down into the sofa afterward told me I still kept a part of myself on sentinel duty. Healing isn’t erasing; it’s building enough rooms that the sentinel finally has somewhere soft to sleep when the watch ends.

In March, Nana called with a cough and a demand. “Come for Sunday dinner. I made stew.” I drove to Maple Bridge with windows cracked, the world thawed into mud and promise. She opened the door with her cane like a scepter. We didn’t talk about my parents. We talked about the stubbornness required to crochet a straight edge and the merits of cardamom in coffee. After dessert, she went to the hall closet and returned with a bundle of manila folders tied with twine.

“These are copies,” she said. “The originals are with my attorney. Don’t make it a movie in your head—I’m fine. But I like my ducks with their little bow ties on.” Inside: a simple trust, the beneficiary named without fanfare. Not a fortune, not a trap—her bungalow, her little account fattened with decades of yard sales and birthday money, a list of bequests to the church bake table and the animal shelter. “They’ll be mad,” I said, because honesty with her was how we loved.

“They are already mad,” she said. “This way their anger has something decent to bounce off of.” I didn’t cry, but something in me sat down on the floor and rested.

On the way back through town, I drove past my parents’ house. The lawn was a winter color without name, not brown, not green, not dead, just paused. The letter J lacrosse stick was still mounted in the hall behind the glass you could see from the street if you knew where to look. I parked one block over, not because I wanted to go in, but because I wanted to know that if I ever did again it would be by choice, not compulsion. I sat there with the engine off and repeated my three words in the cab like a prayer you teach to a child: No. I’ve made other plans.

Spring at the A‑frame smelled like thawed earth and paint. I stood on a ladder and brushed a new coat on the trim while podcasts mumbled in my pocket. Sarah and Tom came over with seed packets and instructions about deer netting. We planted tiny lettuces in a raised bed and named them like ships for luck. Priya lost a client and cried on my sofa and fell asleep under Nana’s throw; in the morning she made eggs with the wedding silver because healing is a breakfast food.

One afternoon a heavy envelope appeared in Box 42—a letter from Dad’s lawyer addressed to Sable, copy to me. It announced their “intention to pursue reconciliation through ecclesiastical mediation.” I read that phrase twice. The lawyer had chosen church like a new venue for control, because shame needs an audience. Sable’s response was three sentences of legal steel: my status as managing member, the active protective order, the prohibition on alternate forums that attempted to override law. She cc’d Nana’s attorney for sport. Nana left me a voicemail that evening: “Let them take it to church. I’ll bring the program and a microphone.”

April brought rain that wrote cursive on the deck and a contractor named Luis who laughed when I told him I’d installed the strike plates myself. “They’re straight,” he said, impressed. He helped me replace the unsecured loft railing with something that looked like it belonged in an architectural magazine and would keep sleepy midnight feet from doing something dramatic. We stained it together with the last packet from the loft box and ate sandwiches with stained hands on the steps while clouds boiled up over the ridge.

I began to host small weekends for women I loved who didn’t know how to ask for a pause. We hiked the easy trail Sarah swore by and learned the names of wildflowers from a map Luz framed for me. We watched bad movies and cut onions and talked about the way families pretend boundaries are cruelty. On Sunday afternoons they left with the code and permission to come back without asking. My guest rooms became less about me having witnesses and more about me witnessing others—how we all glow when we’re not dimming ourselves to fit a photograph we were never invited into.

In May, I received a typed letter from Mom. Not in her voice, in her lawyer’s—apology without confession, regret without specifics, the word “misunderstanding” employed like a Band‑Aid on a broken pipe. Sable sent her our invoice for the time spent reading it. Dad tried a payment to the utility company; it bounced; the system sent me a notification with the cheerful tone of a calendar reminder. I laughed for a full minute that felt like a summer.

The mountain wears summer like someone finally exhaled. The deck grew warm enough for bare feet at night. Fox kits tumbled in the gully. The hawk taught a young one to circle. I took a photo in late golden hour—mote‑filled light, dust from the beam sparkling like a galaxy you can stand under. I didn’t post it. I sent it to Nana. She replied with a heart and then, “I made cardamom coffee. Come down Sunday.”

I did. She had cleaned out a drawer and labeled it FAITH in looping caps with a placebo middle initial just to make me laugh: F. A. I. T. H. She placed inside a key to her bungalow, a rose‑printed handkerchief, and a pack of wintergreen mints. “Just in case,” she said. “I don’t know what case, but one always shows up.”

June wrote itself into the guest book in messy ink from people I loved. Luz got a job offer and accepted it on my deck at 9:12 p.m. exactly as bats flicked past like paper airplanes. Priya’s ex sent a long email titled “Closure,” and we roasted marshmallows and deleted it, because closure has to be a door you close yourself. Gabe met someone who laughed at spreadsheets and we toasted with seltzer while he built her a budget called JOY in a tab that balanced with common sense and a little chaos.

I kept waiting for the tremor in my spine that signaled my family would break the order like weather breaks a plan. It never came. Instead: silence. Not empty; fertile. I took it and planted a dozen small habits—stretching on the deck at sunrise, taking evening walks to the mailboxes even when I didn’t expect anything, keeping the guest beds made, letting the living room be messy for a day without translating it into failure. I set my phone on Do Not Disturb at 9 p.m. and survived.

In July, High Timber held a town picnic in the park by the creek. I brought Nana’s silver serving spoon and my grandmother’s chili and watched kids run through sprinklers while a bluegrass band tuned under a pop‑up tent. The deputy who’d stood in my doorway ate two bowls and asked sheepishly if the recipe was a secret. “It is,” I said, “but it’s also yours.” He laughed, and I emailed it to his official address with the subject line: FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY.

I met a woodworker named June (the month, not the gender), who could tell the age of a tree by smelling a plank and drove a truck that coughed like a dragon in the mornings. We talked about knots like they were poetry and about how you can’t make a joint stronger by yelling at it. June taught me to cut dovetails on scrap, my hands finding a new version of precision that didn’t care about fonts or brand decks. “Wood remembers,” June said, fingertips resting on a board. “So be kind to it.” For the first time in my life, I believed I could build something that would hold weight without asking permission.

August was a long breath. I visited Nana for iced tea and let her nap in her chair while sunlight sold illusions through lace curtains. Mom texted me a photo of a cake she’d baked with the caption “Thinking of you.” I heart‑reacted. Dad sent nothing. Julian posted a picture from a leased apartment with an air conditioner draped in a sheet, the caption a quote about perseverance. Belle sent a photo of a nursery they’d assembled themselves in neutral grays and a note that said, “Our lease is in my name.” I replied, “Good.”

The first day of September wrapped the mornings in chill again. The deck lights came on earlier, and the pep in peppermint felt seasonal instead of defensive. I printed one more page and slid it into the frame behind the door: the court’s notice that the protective order had been renewed by default—no appearance required—because no violation had occurred and because we’d filed our exhibits like people who know how to keep a ledger.

Nana came up mid‑September, cane tapping the deck like a metronome. I had worried about the stairs, but she handled them with the stubborn grace of a woman who once kept a house without a dishwasher and outlived three administrations. We ate soup from bowls too pretty for soup and watched the valley turn late‑day blue.

“Do you miss them?” she asked, because love asks the only question that matters.

“I miss the idea of them,” I said. “But the idea never existed.” She nodded, satisfied and sad, which is the adult way to nod. She fell asleep under the pine‑green throw with her mouth open, the soft, unguarded sleep of someone who knows the door is locked from the inside and the porch light is on.

October painted the ridge with fire. I split kindling under a sky so blue it hurt. June helped me build a narrow bench for the entry, one board that fit the angle of the wall like it had been waiting for a century. We oiled it until it gleamed like a calm lake.

I thought about writing an essay about all of it—boundary as liturgy, strategy as care—but the thought of turning it back into content made something in me stubborn. The deck didn’t need to be a metaphor. It was a place I stood with cold boards under my feet and hot mug in my hands and breath making clouds that dissolved without anyone liking them.

News

November 2nd, 1944. 3:47 p.m., somewhere over Czechoslovakia—and Lieutenant Bruce Carr watches the oil pressure needle fall to nothing as black smoke curls past the canopy of his P-51 Mustang.

November 2nd, 1944. 3:47 p.m. Somewhere over Czechoslovakia, Lieutenant Bruce Carr watches the oil pressure gauge drop to zero. Black…

One pilot in a p-40 named “lulu bell” versus sixty-four enemy aircraft—december 13, 1943, over assam.

At 9:27 a.m. on December 13th, 1943, Second Lieutenant Philip Adair pulled his Curtiss P-40N Warhawk into a climbing turn…

0900, Feb 26, 1945—on the western slope of Hill 382 on Iwo Jima, PFC Douglas Jacobson, 19, watches the bazooka team drop under a Japanese 20 mm gun that has his company pinned. In black volcanic ash, he grabs the launcher built for two men, slings a bag of rockets, and sprints across open ground with nowhere to hide. He gets one rise, one aim—then the whole battle holds its breath.

This is a historical account of the Battle of Iwo Jima (World War II), told in narrative form and intentionally…

At 0700 on October 4th, 1943, Colonel Hubert Zmpy stood on the hard stand at RAF Hailworth and watched mechanics fuel 52 Republic P-47 Thunderbolts for a bomber escort run deep into Germany.

Just after dawn on October 4th, 1943, Colonel Hubert Zemke stood on the hardstand at RAF Halesworth and watched mechanics…

THE DAY A U.S. BATTLESHIP FIRED BEYOND THE HORIZON — February 17, 1944. Truk Lagoon is choking under smoke and heat, and the Pacific looks almost calm from a distance—until you realize how many ships are burning behind that haze.

February 17, 1944. The lagoon at Truk burns under a tropical sky turned black with smoke. On the bridge of…

A B-17 named Mispa went over Budapest—then the sky took the cockpit and left the crew a choice no one trains for

On the morning of July 14, 1944, First Lieutenant Evald Swanson sat in the cockpit of a B-17G Flying Fortress…

End of content

No more pages to load