“I didn’t invite you. Get out of here.”

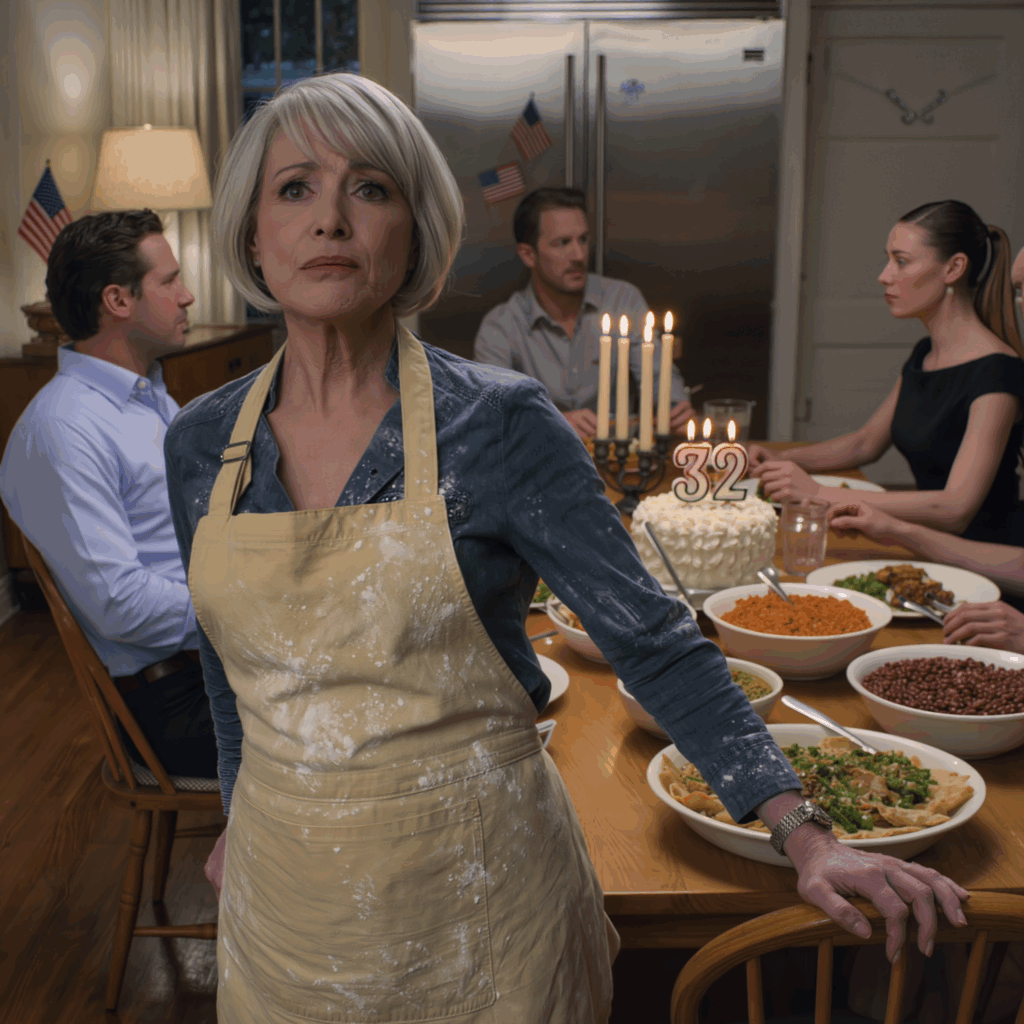

Khloe’s scream split my living room like glass.

My hand was on the back of a chair at the table I’d been preparing since five a.m. Candles lit. Dishes steaming. The whole room smelled like green‑chile enchiladas—the kind she swore only I could make.

I tried to sit. She looked at me like I’d wandered in off the street.

“What are you doing?” Her voice was ice. “No one called you. This is my party.”

I looked at Dan. My son stared at his plate. Not a word. The room went heavy and still. I stood in my apron with fourteen hours of work aching across my shoulders and thought, so this is how it is—humiliated at my own table in my own house.

“Please forgive the interruption,” Khloe said sweetly to her guests. “You know how mothers are. Always in the middle of everything.”

Laughter. The kind that pretends to be polite.

I turned toward the door. The knob was cold in my hand. I should have left. Instead, something lit inside me—older than rage. I breathed, put the moment in my pocket like a stone, and decided to tell you how I got here before I tell you what I did next.

My name is Eleanor Hayes. I am sixty‑four years old. This house is mine.

I grew up the eldest of seven, a couple hours from the city, a white farmhouse with a tin roof that sang when it rained. By fifteen I could run a home—stock a pantry, stretch a stew, put starch in a shirt so crisp it could stand on its own. My mother said I was born with golden hands and a back that didn’t know the meaning of quit.

At eighteen I married Robert—quiet, strong, a construction man who built walls like prayers and came home with concrete in the creases of his hands. A year later, Dan was born, my dark‑eyed boy who wrapped his fingers around mine and wouldn’t let go. We didn’t have much, but what we had we used twice.

When Dan was six, the scaffolding went wrong. Robert left for work and didn’t come home. I learned how silence sounds when it moves in for good—heavy, stubborn, a new piece of furniture no one asked for.

I did laundry, then ironing, then cooking. Eighteen‑hour days, calluses like armor. I learned to say yes to anything that paid cash by Friday. Dan never went hungry. He never missed school. We read library books on the porch and counted airplanes in the night. I saved coins in a coffee can until the metal sang with them, and at ten years old my boy stood in the yard of the little house I bought and said, “Is it really ours?”

It was small, but I painted every room myself—eggshell in the hall, sky blue in the tiny bath, a warm yellow in the kitchen because Robert once said food tastes better in sunlight. I fixed leaks with tape and prayer, learned shut‑offs and breaker boxes, planted roses against the fence and a lemon tree by the kitchen window. The first bloom smelled like we’d done the impossible.

Dan grew tall here. Birthdays on the back lawn. Clay volcano for fifth‑grade science erupting across my table. A diploma pinned to the wall with a bent nail because the frame could wait. I thought I had done something right.

Then came Khloe. Pretty, quick to laugh, a perfume that smelled like peaches. Polite the first day I met her. She called me Ms. Eleanor and brought daisies from a gas‑station bucket, and I stuck them in a jar and said thank you as if the jar were crystal.

They married in my backyard under a dollar‑store arch draped with carnations and a string of warm lights that made the lemon leaves glow. I cooked for everyone. She hugged me and said I was the best mother‑in‑law anyone could ask for. I believed her. I believe people who say thank you.

Six months later, Dan came by while I watered the roses. His tie was loose. His eyes were tired.

“Mom, rent’s insane. Could we stay a little while? Just until we save a deposit.”

“Of course,” I said. Because that’s what mothers say. Because I remembered choosing between the light bill and shoes that fit. Because love sometimes sounds like yes before you know the price.

I gave them my big bedroom with the bathroom and moved into the storage room with the tiny window. I stacked my life into plastic tubs, labeled them in block letters, told myself it was temporary—three months, six at most. Then I started moving my habits to make space for theirs.

The little comments came first.

“Eleanor, these pots should go somewhere else.”

“The table would look more modern on the other wall.”

“That tablecloth is a little… old.”

I slid pots. I moved the table. I folded the embroidered cloth my mother made and tucked it away like something dangerous.

Then the big moves. I came home from the market and my rocking chair—the one Robert gave me when Dan was born—was gone.

“I put it in the garage,” Khloe said, scrolling her phone. “It didn’t match. I got a new sofa. Looks nicer.”

“Where’s the chair?” I asked again, as if repeating the question could rewind time.

“In the garage,” she said, slower. “It’s dusty anyway.”

My kitchen followed. Gray subway tile, white cabinets, stainless‑steel sink. Clean. Modern. Cold as a doctor’s office. “Now it actually makes you want to cook,” she said. She didn’t lift a pan for weeks.

They didn’t save. They shopped. He traded the car. She added shoes to a closet that seemed to multiply. I cooked, washed, waited up. My shows disappeared under their remote. My friends stopped coming by because the house was always full of hers. People I didn’t know walked in and out like they had a key.

Once, a woman I’d never met smiled at me over the fridge water and said, “Khloe is so lucky to have help.”

Help.

I became the kind of quiet that makes other people louder. At three a.m. after one of their parties, I cleaned wine rings and crumbs in the dark while the house ticked and the refrigerator hummed—my own home sounding like a hotel hallway.

When I finally tried to set a boundary—“Dan, it’s been a year. Have you looked for places?”—he told me I was being sensitive. “We pay the utilities, Mom,” he said. “It’s all of our house.”

When Khloe thought I couldn’t hear, she told someone on the phone, “It’s free. We don’t pay rent, don’t pay utilities, don’t pay for anything. I just put up with the old woman.”

The knife slipped from my hand into the sink. The sound was small and sharp and true.

That should have been the moment. It wasn’t. The moment was her birthday.

She invited twenty‑five people. Gave me a menu as long as my arm. Asked me to pay for the groceries because she and Dan were “saving.” I spent two hundred dollars of my pension and fifteen hours cooking. At six‑thirty, she told me to keep to the kitchen so she could greet her guests “without interruptions.”

I pressed forty tortillas by hand and stacked them in a towel so they’d steam soft. I chopped cilantro until the house smelled green. I made three salsas—roasted, raw, and one that bites after you swallow. I simmered charro beans low and patient like the way you talk to a child who doesn’t yet understand. The tres leches sponge rose level and golden as a summer evening. I whisked meringue until my shoulder burned and kissed the peaks with the back of a spoon to make little ridges that would catch the light.

From the pass‑through I watched them eat like a caterer who forgot her polo. Khloe sat at the head of my table in my seat and raised a glass. “To my house and my family,” she said. Dan’s smile was small. Mine didn’t exist at all.

When I tried to sit in the one empty chair, she screamed.

“Get out. I didn’t invite you.”

I looked to Dan. He couldn’t look back. A friend of hers studied the ceiling as if help might be written there. Her father took a long drink and polished the rim with his thumb.

Then Khloe’s voice turned gentle, a kindergarten teacher’s tone. She told the room I was “a little confused lately.” That I didn’t always understand where I was.

Pity faces. The kind that offer nothing and expect thanks.

I went to the kitchen sink and ran cold water over my hands until they hurt. Dan came in to tell me to calm down. To rest. That I’d feel different in the morning. He said the party shouldn’t be about me. He said things he’d never say if the story were told with the names switched. I let him talk. I watched Sharon’s light next door. I envied the quiet.

For a week, they acted like nothing happened. Then Khloe told me her parents were coming for two weeks and would stay in my room. I moved my life to the laundry room—old mattress on concrete, pipes roaring like freight trains whenever anyone flushed. Mrs. Helen handed me a silk blouse and a list. Mr. Arthur told Dan how much they must be saving with “help in the house.” Dan laughed and said I was useful.

Useful.

On their last morning, I boiled coffee strong and stood in the steam until my eyes watered. When the house emptied out, I walked into my room and shut the door. I stood with my back against it like someone might try to take it back by force. Then I stripped the bed, opened the window, and let the lemon tree breathe into the air.

Khloe exploded when she came home. “How dare you,” she said, and I finally learned that a dare can be accepted by standing very still.

They decided the “adult” solution was to sell my house. I said no. They brought a realtor; I sent him away. They said Dan had rights because he lived here. I said the deed had one name. Mine. That night I took the bus downtown and found a lawyer whose office smelled like paper and ink and long fights. I slid my hands across his desk and told him the whole story. He slid papers back—homestead declarations, fraud alerts at the recorder’s office, a letter that said any listing attempt would be considered interference with property.

I slept that night with the envelope under my pillow. It rustled like a guard dog.

Khloe said I would die alone. I said I’d take peace over pity.

The next weeks were a quiet war. Doors. Silence. Footsteps at odd hours. I stopped cooking for them. I washed only my clothes. I ate at the table with my plate set at the spot where the light falls warm at four in the afternoon.

Then came the late‑night argument through drywall thin as paper: she wanted him to choose—me or her. “She’ll cling to that house until she dies,” Khloe said. “I won’t spend my life in another woman’s shadow.” He said I was his mother. She said she was his wife. He said nothing that could hold both truths at once.

By morning, they had a tiny apartment on Maple with windows that faced a brick wall and a lease with move‑in next Saturday. Dan hugged me at the door and said he loved me. I told him I hoped that stayed true when things got hard.

After the truck turned the corner, the house exhaled. I heard the quiet settle back into the walls like a long‑absent tenant turning a key. Sharon brought sweet bread and coffee. We ate in the yellow kitchen and didn’t pretend. She asked how I felt.

“Free,” I said. The word fit in my mouth like bread still warm.

The call came a month later. “Mom, Khloe’s pregnant. Rent’s high. Can we come back just until the baby—”

“No,” I said, watching a bee fuss with the lemon blossoms. “Not here.”

“It’s your grandchild.”

“I know. I’ve learned I can’t help anyone if I’m broken.”

Silence. He said he understood. I hung up and put the phone in the drawer with the takeout menus and a tape measure and a Phillips screwdriver, and it felt like a declaration.

Months went by. No calls. No visits. The house and I learned each other again. I painted the kitchen Robert’s soft yellow. I rehung the clock that had kept time through everything and replaced its batteries like a promise. I put my mother’s embroidered tablecloth on Sundays and didn’t worry about stains because stains are just proof you were here.

I joined Sharon at the community center on Tuesdays to teach a cooking class for people who think dinner is only ever a drive‑thru. We made soups you can stretch and a roast chicken you can turn into three different meals if you know what you’re doing with onions. I watched teenagers taste cilantro for the first time and decide they had opinions. I watched a widower learn that grief can’t stop your hands from making bread.

Six months later, Dan knocked. He had a baby girl in a pink blanket and a look that had learned humility the hard way.

“This is Eleanor,” he said. “I named her after you.”

He sat, eyes dark with no sleep and too much fear. “Khloe left,” he said. “She said she’s not ready to be a mother. I don’t know what to do.” Tears slipped and he let them.

I wanted to take the baby and say yes to everything because love is a reflex you can’t unteach. I didn’t.

“I’ll help,” I said, “but with boundaries. I won’t be your lifeline. You can visit. I’ll watch her for a few hours. I’ll teach you what I know. But my life is mine.”

He nodded. “I’m sorry,” he said. “For all of it.”

“I forgive you,” I said. “Forgiveness isn’t forgetting. It’s learning.”

We learned a rhythm. He worked doubles and slept on my couch two nights a week. I kept the baby those nights and taught him to swaddle, to burp, to live on crockpot soups and thrift‑store onesies. I showed him how to stretch a dollar without snapping it in half: rice cooked in broth, beans with bay leaf, a bag of carrots turned into three sides. I showed him how to pack a diaper bag as if a storm were coming and the only way through was readiness.

On Saturdays he arrived with diapers and a smile that looked like the boy who used to bring me dandelions and call them flowers. We walked the neighborhood with the stroller that squeaked like a cricket. Neighbors paused to lean into the shade of the canopy and gasp at the name.

“She’s named after you?” they’d ask.

“She is,” I’d say, and there was a quiet inside that sentence that felt like mending.

The old patterns tried to creep back in—little asks that grew larger, favors shaped like obligations, a panicked text that hoped I’d say yes before I had time to decide. I said no more often than I said yes. I said it kindly, and then I said it again if I had to. Boundaries, I learned, are fences with a gate you unlatch from the inside.

Khloe didn’t call. When she finally did, the baby was almost one. She wanted photos. She wanted to meet for an hour “as a friend.” She wanted Dan to understand how hard things had been for her. He met her at a coffee shop. He came back with a face I recognized from when he was twelve and learned his father wouldn’t be at the school play—together, but missing.

“Did you tell her about Eleanor’s first steps?” I asked.

He blinked. “No,” he said. “I told her how much diapers cost.”

We laughed. We cried. We made more soup. He brought over a stack of paperwork for a parenting plan the court clinic had them draft: exchange times, holidays, the address of the neutral drop‑off lot behind the library with cameras that see better than people do. He asked me to look it over. I underlined where it said respect.

On the baby’s birthday, the three of us stood in my yellow kitchen and blew out one candle stuck in the top of a cornbread muffin because I’d run out of sugar and didn’t feel like going to the store. The baby shrieked at the flame, then at our faces, then at the taste of butter. It was perfect.

Later that night, when the house was quiet again, I brewed tea and sat by the window. The stars were stubborn and bright. The lemon tree moved a little in the dark like it was agreeing with me. I thought about the word useful and all the ways it had been used against me. I thought about the word mother and all the ways it still meant work. I thought about the chair.

You want to know what I did the night Khloe told me to leave my own table? Here is the truth I keep under my tongue like a lozenge for bad days: I didn’t slam a door or throw a plate or raise my voice. I found the part of myself I’d abandoned in a storage room, walked her to the living room, and sat her down in my rocking chair. I said, Try again. I said, Stay. I said, We are not leaving. After that, everything else was logistics.

There were days I missed the noise because noise pretends to be company. There were days I wanted to call first and forgive later. There were nights when loneliness felt like a draft under the door you can’t find the source of. But then morning would come, and so would the kettle and the lemon tree and a neighbor walking her dog and a list of things to do that belonged only to me.

I refinished the dining table. Sanded it down until the rings and knife nicks told the history I was willing to keep and nothing more. I set two chairs, one for me and one for anyone who came with respect. I hung a photograph of Robert above the pass‑through, the one from our second spring when we couldn’t afford a photographer and his coworker used a disposable camera and still somehow caught us in a laugh I can feel if I close my eyes.

Khloe tried once more. She arrived with a realtor who didn’t know better and a voice that did. I opened the door. I smiled. I asked him if he liked coffee and if he’d like to read a deed. He left before the pot finished brewing. She hasn’t tried since. A month later I got a letter from a law office with a logo that looked expensive. It suggested mediation about “joint housing solutions.” I put it in the drawer with the screwdriver and the tape measure. I wrote back one sentence: The house is not a joint anything.

At the community center, a woman with a laugh like a bell said her landlord was raising rent again. I showed her how to make a lease binder—copies of everything, receipts tucked in a sleeve, a page where you write down each conversation. Power looks different when it’s organized. She cried when she got her deposit back. We celebrated with coffee so sweet it could have been candy.

Dan started paying his bills on time most months. He kept a small ledger like I taught him, a notebook with boxes and arrows that turned the terrifying into math. He switched to a cheaper phone plan and stopped eating his paychecks in drive‑thru lines. On Fridays he’d text me a photo of the baby asleep in her car seat with a caption that said, We made it.

Sometimes I saw Khloe’s car at the daycare. Sometimes I didn’t. Once, she watched me buckle the baby into my backseat and didn’t come over. Another time she did. She said she liked the baby’s shoes. I said I did, too. The conversation was half‑stitched and that was enough.

People ask if I’m lonely in a house this quiet. I tell them the truth. Some evenings, yes. Most mornings, no. Freedom hums at a lower volume than chaos. It takes a while for your ears to trust it.

I put the rocking chair where the light hits just so at four in the afternoon. I keep my blue mug with the white flowers in the back of the cabinet because some things are sweetest when they are only for you. I make tres leches on Sundays when the baby comes because that’s what love tastes like in this house. I plant marigolds along the roses because my mother said they keep bad things away and because I like the stubborn marigold orange against the fence.

When I pass the gray tile in the kitchen, I touch it and smile. It used to feel like a wound. Now it’s a story. This is the room I took back. This is the room where my life started again.

A letter came addressed to Dan one afternoon—a collection notice in a tone that thinks shame will pay a bill. I set it aside and when he arrived I handed it to him and didn’t say a word. He read it. He didn’t flinch. He asked for a pencil. He called, asked for a payment plan, made one, and stuck to it. That is also a kind of apology.

At the library exchange lot—cameras watching, lines painted bright like rules you can actually see—Khloe arrived one Saturday with a stuffed bunny and a bag that finally had diapers in the right size. She said she was trying. Dan said he could tell. I held my breath without meaning to and then let it go the way you do when a storm passes without breaking the glass.

On the anniversary of Robert’s death, I made his stew—the one with cumin and two kinds of potatoes because he always said one kind is for sensible people and two kinds is for joy. Dan came over after work and we ate in the yellow kitchen with the clock that ticks like a heart. He told me stories about his daughter I hadn’t seen on Saturdays: how she says “lello” for yellow, how she kisses the picture of the lemon on the dish towel, how she taps the window when it rains and says, “Papa, listen.” We listened. The roof sang.

Sometimes, late, I rehearse the words I’ll say if Khloe ever walks in and calls it her house. I don’t need them, but I keep them polished like silver. Not for her. For me. Because saying the truth out loud keeps it true inside.

Because in the end, it wasn’t a lawyer or a realtor or even the deed that saved my life. It was a single decision made with both hands on a chair—this is mine—and all the ordinary, stubborn choices that followed: paint the kitchen, answer the phone, say no, say yes, buy carrots, make soup, walk, sleep, wake, rock the baby, breathe.

“Get out,” she said that night.

I didn’t.

I stayed.

And that has made all the difference.

News

November 2nd, 1944. 3:47 p.m., somewhere over Czechoslovakia—and Lieutenant Bruce Carr watches the oil pressure needle fall to nothing as black smoke curls past the canopy of his P-51 Mustang.

November 2nd, 1944. 3:47 p.m. Somewhere over Czechoslovakia, Lieutenant Bruce Carr watches the oil pressure gauge drop to zero. Black…

One pilot in a p-40 named “lulu bell” versus sixty-four enemy aircraft—december 13, 1943, over assam.

At 9:27 a.m. on December 13th, 1943, Second Lieutenant Philip Adair pulled his Curtiss P-40N Warhawk into a climbing turn…

0900, Feb 26, 1945—on the western slope of Hill 382 on Iwo Jima, PFC Douglas Jacobson, 19, watches the bazooka team drop under a Japanese 20 mm gun that has his company pinned. In black volcanic ash, he grabs the launcher built for two men, slings a bag of rockets, and sprints across open ground with nowhere to hide. He gets one rise, one aim—then the whole battle holds its breath.

This is a historical account of the Battle of Iwo Jima (World War II), told in narrative form and intentionally…

At 0700 on October 4th, 1943, Colonel Hubert Zmpy stood on the hard stand at RAF Hailworth and watched mechanics fuel 52 Republic P-47 Thunderbolts for a bomber escort run deep into Germany.

Just after dawn on October 4th, 1943, Colonel Hubert Zemke stood on the hardstand at RAF Halesworth and watched mechanics…

THE DAY A U.S. BATTLESHIP FIRED BEYOND THE HORIZON — February 17, 1944. Truk Lagoon is choking under smoke and heat, and the Pacific looks almost calm from a distance—until you realize how many ships are burning behind that haze.

February 17, 1944. The lagoon at Truk burns under a tropical sky turned black with smoke. On the bridge of…

A B-17 named Mispa went over Budapest—then the sky took the cockpit and left the crew a choice no one trains for

On the morning of July 14, 1944, First Lieutenant Evald Swanson sat in the cockpit of a B-17G Flying Fortress…

End of content

No more pages to load