I was awake before the phone rang at 2:17 a.m., the kind of waking that has nothing to do with alarms or coffee—just a pressure at the base of the spine, some old animal instinct that knows when a life is about to split in two.

“Mrs. Reynolds, this is Mercy Hospital,” the voice said, calm in that way that means calm is over.

The house held still around me, that Cleveland quiet before snow, when the furnace ticks and the old flag on the porch makes a faint sound against its pole. I found my shoes, my keys, the folder where I kept James’s insurance policy, and the extra set of glasses I never liked. I took the long way to the hospital because I couldn’t handle the short one.

By sunrise I was under fluorescent lights, holding a coffee I couldn’t swallow, watching those automatic doors breathe open and shut like lake water against a breakwall. My son—thirty-eight, a litigator with good manners and a shy smile, a man who brought me chrysanthemums every Wednesday because he said midweek needed warmth—had a word attached to him that didn’t belong. Aneurysm. I tried to carve a space around it that would make sense, but the word refused to shrink.

By noon, the elevator chimed and the doors split to reveal Sophia—oversized sunglasses, immaculate black, the curated hush of a magazine spread. “Traffic,” she said first, like it was a script. Then: “And I had to find someone for Lucas.”

I nodded. I’d already called the school. Our eight-year-old had math at ten and art at one. He would be met at the curb by Mr. Elkins, who’d keep him until I could get there. Mothers sense the shape of a day even when it’s folding in half.

At the chapel doors I met Thomas Bennett, who had been James’s friend since law school and, more importantly, the kind of man who carried his promises in a leather planner and kept them there. He hugged me once, like a person not performing anything, and said, “Some matters in the will need immediate attention.” The word immediate thinned the air.

The funeral was the kind of American ritual small towns still know how to do: flags at half-mast on Main Street, police officers stopping traffic in their dress uniforms, neighbors setting hot casseroles on long tables that clinked as if grief made dishes ring. A brass trio played “Amazing Grace” under a sky so pale it looked washed. I kept an arm around Lucas, whose small fingers found mine without looking. His mother’s expressions changed like jewelry—warm for the firm’s partners, cool for James’s high school buddies, solemn for the pastor who had baptized him under a cross of stained glass and summer dust.

After the service, when the coffee turned bitter and the punch tasted pink, Thomas pressed a sealed envelope into my palm. My name was written in the old looping script I taught a boy who once sat on a kitchen stool, heels swinging above the tile. “Read it alone,” Thomas said. “And—Eleanor—trust your instincts about Lucas.”

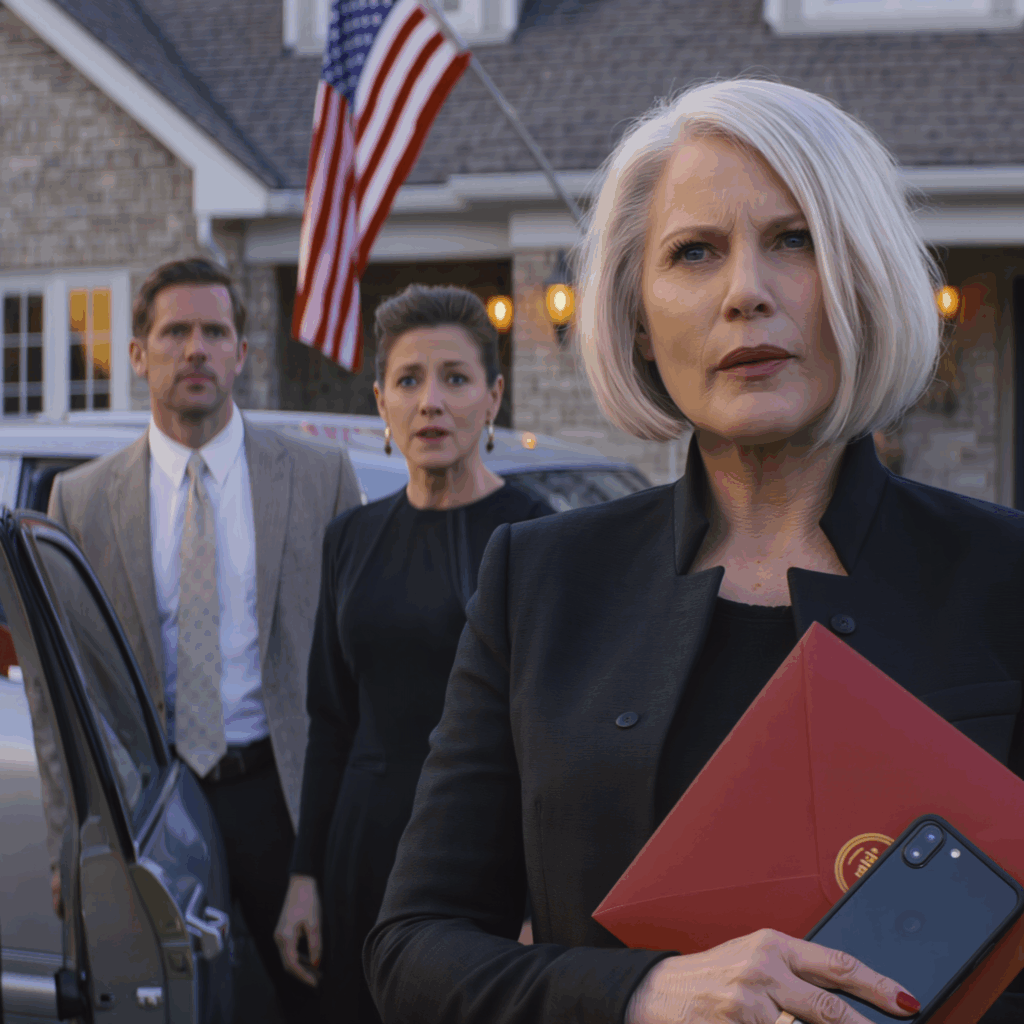

Two hours later we met at a conference room with too much glass and not enough air, the kind of downtown office where everyone’s shoes echo like they’re walking on stage. Sophia dabbed at eyes that weren’t red and spoke of “moving quickly for the sake of the child,” of “fresh starts,” of “healing trips” that sounded a lot like Miami with receipts. Pens clicked. Pages fluttered. Thomas adjusted his glasses.

Then a single sentence—quiet, precise—placed the house, both cars, and a bank account under one name I recognized in my bones. Mine.

I said nothing. In the space where I might have breathed too loud, I discovered the shape of relief. It didn’t feel like victory; it felt like placing a hand on the railing of a staircase in the dark and finding it’s where you need it, steady and sure. I looked at a photograph of James on the wall—my boy smiling without showing his teeth—and I understood why he had been so careful these last months. He had seen something. He had prepared something.

And I was grateful that I’d said nothing to anyone until the words lived in air that could hold them.

That night, I drove home along Euclid while the courthouse eagle lit up against the November dusk. On my porch, the small flag by my geranium box tugged at its pole and the chrysanthemums in their Wednesday jar drooped like they understood. I placed the envelope on my dining table, beside the wooden bowl James carved in seventh grade, the one that still holds our keys. Then I made tea, though I didn’t drink it.

I sat.

And I opened what my son left for me to read when no one else was looking.

Inside: a letter, three pages, written in a steadier hand than his everyday notes. It began like a lawyer and ended like a child.

Mom,

If you’re reading this, it means my plan has to stand up without me. You taught me to build things that last. This is my attempt.

There’s a trust—documents with Thomas. The house, the cars, and the account are titled to your name for a reason: you are trustee. The beneficiary is Lucas. Keep it quiet until you need to be loud. If you are reading this, I think you’ll have to be both.

He explained it in clean detail: a revocable trust that became irrevocable upon his death, a guardianship nomination naming me as Lucas’s standby caregiver, an educational trust with a 529 plan already seeded, a durable power Thomas could activate to protect Lucas’s day-to-day if conflict arose. Words like “independent trustee” and “letter of wishes” mixed with “baseball glove” and “Wednesday flowers.” He had attached a separate letter of intent, written in the plain language of a father who knew his son’s allergies, his favorite bedtime book, the location of the flashlight by the back door.

Then he wrote a sentence so simple it made my throat hurt.

Mom, I need you to protect Lucas from performance.

I read it twice. I read it standing up, as if the words required posture. And then I read the rest.

He described concerns he had not shared out loud: money moved around in a way that felt like show; travel plans that grew brighter when arguments dimmed; a pattern of late fees on the card he paid off every month. He did not ask me to fight. He asked me to stand. To anchor. To hold.

I put the pages back in their envelope and stacked them on the folder with the insurance policy. I opened my back door and stood a minute in the November cold, looking at the small rectangle of lawn where Lucas learned to ride a bike between my maple and the neighbor’s fence. The porch light illuminated the empty space where the plastic ramp once sat. The air smelled like leaves going to paper. I breathed.

In the morning, I met Lucas for waffles and told him we were going to start a new Wednesday tradition: his pick for breakfast, my pick for flowers. He liked the idea of picking both.

He asked, because children ask what they already know the answer to: “Can I stay with you for a while?”

“Yes,” I said. “You can stay with me for a while.”

That afternoon, Thomas filed the necessary motions—a petition for temporary guardianship consistent with James’s nomination, the trust documents that kept the assets held for Lucas’s benefit, and a proposed schedule that allowed Sophia to see her son. We didn’t pit anyone against anyone. We didn’t even raise our voices. We stacked paperwork the way you stack sandbags before a flood.

Sophia called that evening with the sweet tone she uses for people who might quote her. “Eleanor, I think we should talk about what’s best for Lucas,” she said. “Children need sun in the winter.”

“Children need home,” I said. “We’ll talk tomorrow. With Thomas.”

I’d forgotten how good it felt to be the grown-up in the room.

In the weeks that followed, grief did what grief does: it rearranged everything from light switches to grocery aisles. Lucas cried when the first snow stuck and then laughed because the sound of ice under his boots made him feel big. At bedtime, he arranged his stuffed otter and his two-dollar plastic trophy for “Most Improved” like they were a council of elders. We played “I Spy” with the pictures on my hallway wall. We ate chicken noodle soup from the recipe card written in my mother’s style—blue ink, looped J’s, a teaspoon of kindness that wasn’t written down but lived in every spoonful.

On Wednesdays, we bought chrysanthemums. He chose orange. At the flower shop, the owner, a woman with silver hair pulled into a pencil bun, gave Lucas a tiny flag pin because he had admired the one by the register. “It keeps the shop lucky,” she told him, and he pinned it on his backpack with great ceremony.

We didn’t avoid James. We made space for him. We told stories that remembered the before in a way the after could hold. We said his name at the table like it was a chair no one needed to pull out for him because he already sat with us.

Then came the hearing.

The courtroom felt like the inside of a well-kept book: polished wood, good light, the whisper of pages turned by people who do this every day. The judge wore reading glasses low on his nose and had the kind of face that says he has seen the whole parade but still tips his hat to the marching band. Thomas set his file on the table and that was how I knew we’d be okay; he placed it there like a person unafraid of weight.

Sophia sat across from us in a charcoal dress that would photograph nicely. Her attorney was younger than Thomas and had the eager air of a man who runs stairs before sunrise. He introduced himself and then began to paint pictures with words: about a boy who needed sunshine, about a home that needed fresh rooms, about a future that should be a beach, not a lake.

Thomas waited. He did not interrupt. When it was his turn, he stood and said, “Your Honor, the decedent executed a revocable trust that is now irrevocable. The trustee is Ms. Reynolds. The sole beneficiary is the minor child. We are not here to exclude anyone. We are here to preserve what the decedent built and to implement the plan he set down while fully competent, fully advised, and—if I may—fully a father.”

He offered the documents with that simple gravity that makes paper feel like stone. He spoke of continuity of school, community, doctors. He referenced the letter of intent without reading from it in a way that would turn it into theater. He laid out a schedule that gave Sophia substantial time but not control, and a financial arrangement that paid for Lucas’s needs directly rather than via anyone’s wishlist.

The judge leafed through the stack and asked three questions. The third was the real one.

“Ms. Reynolds, what will you do with these assets?”

I stood. My hands did not shake. “Your Honor, I will do with them what my son asked me to do. Keep Lucas’s life steady. Pay the mortgage here so he can keep his room and his baseball glove where he expects to find them. Fund his education. Maintain the cars until they help us do that, and then sell them to contribute to the trust. I will file every report on time. I will answer every call from his school. And I will send him to sleep each night with fewer worries than he woke with.”

The judge looked over his glasses. His pen hovered, then landed. “Temporary guardianship to Ms. Reynolds, consistent with the decedent’s nomination. Assets to remain in trust for the minor child. Ms. Reynolds to provide monthly accountings to the court and to counsel for the mother. Parenting time for Ms. Ward”—Sophia’s maiden name—“as proposed. We will review in ninety days.”

Sophia’s attorney nodded, which is the civilized way of losing. Sophia’s lips curved into a smile that was more a shape than a feeling, and then faltered in the middle as if someone had cut a wire.

We went home.

The next weeks turned into a rhythm. There were drop-offs and pick-ups, the practiced exchange of a child’s backpack and lunch box—objects that can carry more adult temperature than coffee. Sophia arrived on time and sometimes early. She brought snacks that came with tiny toys and a lot of packaging. When Lucas returned, he brought back glitter that would not leave the couch, postcards from somewhere with palm trees, and a new list of things he wanted. We talked about wanting and needing the way you talk about weather in Ohio: it changes, you respect it, you make your plans around it.

On a Sunday, I found a charge on a card I didn’t recognize and a pattern behind it that I did. The trust protected the big things, but Sophia had access to an old joint account James had forgotten to close years ago, one he used briefly when they first married for utilities. The balance was small. The principle was not. I called Thomas. He called the bank. We closed it politely. It felt like dusting the top of a bookshelf: small, necessary, clarifying.

After that, Sophia’s tone shifted. Not icy—considering. The next handoff, she stood in my doorway longer than usual. She looked past me, at the framed school photos, at the tall jar of orange chrysanthemums, at the flag magnet on my refrigerator that holds a drawing of a fish with arms.

“James loved those flowers,” she said, quietly enough that the word love felt like something you could say out loud again.

“He did,” I said. “Every Wednesday.”

She nodded. “He used to call me on his way to your house and say, ‘She’s going to pretend she doesn’t need help bringing the groceries in. Don’t believe her.’ He thought he was funny.”

“He was,” I said. And we both smiled, because the sentence had no enemies in it.

That was when she asked if we could sit down and talk without lawyers. I said yes, but also said Thomas would want a memo after, because I had learned something since the call at 2:17 a.m.: kindness can be real and still write things down.

We sat at my kitchen table like two people in a community college brochure about conflict resolution. She picked at a muffin like it had wronged her. Then she stopped touching it and set both hands flat, palms down, like a person asking the table to tell the truth.

“I know James left things to you,” she said. “I know it means I don’t… decide anymore. I know you think I perform.”

“I think you scan,” I said, and she surprised me by closing her eyes and nodding.

“It’s a habit,” she said. “You grow up poor enough and scanning becomes survival. You walk into a room and count exits, faces, chances. You marry a man like James and the scanning doesn’t stop; it gets… prettier.”

“Lucas needs fewer mirrors,” I said. “He needs more hands.”

She looked at the daisies on the window ledge like maybe they’d answer for me. “I do love him,” she said. “I know people think I love what he is to me. Sometimes I’m not sure I can tell the difference.”

“That is a brave and scary sentence,” I said. “Thank you for saying it out loud.”

After that, nothing changed and everything did. We built a calendar that started to feel like a life instead of a contest. Sophia asked if she could attend the Wednesday chrysanthemum ritual when it was her day. Lucas agreed on the condition that he could still pick orange when the shopkeeper suggested white. She bought orange, and the shopkeeper winked at me as if we’d both seen something shift a degree toward true.

There were setbacks. There always are. A Florida weekend without enough sunscreen. A missed spelling test because a late return turned bedtime into midnight. A temper at my door when a new boyfriend, briefly present, left too fast. But there were also gentle steps in the other direction: a thank-you text without emojis; a suggestion that we split Halloween and both walk the block; a shared laugh at the school winter concert when Lucas, solemn as a senator, adjusted the flag pin on his sweater before he sang “America the Beautiful.”

In January, the court reviewed our arrangement and made it sturdier. The judge looked over his glasses again and told us we were doing well. He told Sophia she had made improvements the court appreciated. He told me I had fulfilled my duties and that the court would trust me with fewer reports. I drove home on roads plowed into two precise lines and felt, for the first time since the phone call, that life was a place we could live in rather than a hallway we kept walking through.

One night in February, I took the envelope out again. I read the letter until I reached the part about performance. Then I pulled out the attached letter of wishes, which I had never read all the way through. It was longer than I remembered. It had sections for school routines, allergies, bedtime songs (he spelled “Edelweiss” wrong and I could hear him doing it), and five paragraphs on baseball. It also had one page labeled, in James’s steady hand: Contingencies.

If X happens, do A.

If Y happens, do B.

Trust Thomas. Trust yourself. Don’t trust quick fixes.

The last line was a sentence I had never heard him say out loud but had felt in every uneven decision of our lives.

Mom, protect the boring parts. They’re where all the love hides.

I laughed, alone in my kitchen, and startled myself by crying the way a person does when she forgets she’s allowed to—fast and soft and done before she goes to find the tissues. When I returned to the table, I pressed my hand to the page like the paper had a temperature I could learn.

Spring came to Cleveland the way it always does, in three false starts and one real one. The street’s American flags turned from winter-stiff to wind-proud, and the porch steps needed paint. Lucas’s Little League team—the Cardinals—announced practice times. I found his glove behind my couch, under the place where glitter had taken up permanent residence, and we softened it with oil while we watched a ballgame on TV. He held the glove to his face and said it smelled like a barn, which he had never seen but described like he had built one with his own hands.

On a Wednesday in April, Sophia arrived early for the flower ritual. She wore a navy jacket and an expression I couldn’t read and didn’t try to. We walked to the shop in a row—Lucas in the middle, his small hand in mine, then in hers, like a metronome. The shopkeeper had set a pitcher of orange chrysanthemums in the front, as if she knew our stride. Lucas picked a bunch with the kind of decisive nod that makes you want to clap.

On the way home, Sophia stopped at my gate. She touched the wrought iron like it was a decision, then looked at me. “I spoke to Thomas,” she said. “About the trust. I understand it better now.”

“Good,” I said.

“I also asked him if there was a way I could contribute, not in money, but—” She stopped, searching.

“In reliability,” I said.

She nodded. “Yes. In the boring parts.”

We built a new plan. She took mornings on her days and drove Lucas to school; I did afternoons on mine and took him to practice. She attended parent-teacher conferences with me, and we learned to sit on the same side of the table, not because the school insisted but because geometry can become kindness when a child realizes the adults are looking in the same direction. She came to our Sunday dinners sometimes and brought salad in a big wooden bowl—James’s bowl, returned with no speech, set in the middle of the table like an invitation to keep being a family in a way we could survive.

That summer, Lucas hit a double that he will tell you could have been a triple if not for the sun. He wore sunscreen like he was being paid to advertise it. We bought orange chrysanthemums every Wednesday until the shop ran out, and then we bought white and pretended they were orange. On the Fourth of July, we sat on lawn chairs in my driveway. I made lemonade that was too tart. A small flag stood in a planter. Fireworks across the lake shimmered like someone shaking sequins off the edge of a dress. Lucas leaned against my arm and asked if stars have a bedtime. I told him yes, and that they are very responsible about keeping it.

In September, we attended a memorial scholarship banquet at the law school where James used to guest-lecture. The dean spoke about public service and about how law is an argument with yourself that you try to win honestly. They announced the Reynolds Scholarship for students who intend to work in legal aid. Thomas had set it up from the life insurance, quietly, the way he does everything. Sophia squeezed my hand when they said James’s name. I squeezed back.

The year turned, as years do.

On the next November morning when the sky washed pale again, we drove to the cemetery with a thermos of cocoa and a small bunch of orange flowers that had somehow kept blooming under the shop’s old awning. Lucas carried them like a folded flag. We stood, we remembered, we said the things we needed to say. On the way back, he asked if the letter was still on my table.

“It is,” I said.

“Can I read it when I’m older?” he asked.

“When you’re ready,” I said.

He nodded, satisfied as if a judge had ruled in his favor.

That winter, Sophia moved to an apartment ten minutes away. Not four states. Not two. Ten minutes. She hung Lucas’s art by the kitchen. She stopped scanning as much. She started planning more. She learned the names of his teammates like they were vocabulary she intended to use in a sentence. She kept being Sophia—interested in presentation, drawn to the glow of places with valet parking—but she also became someone who understood the value of the light in a living room at exactly 5:17 p.m. when homework meets dinner and everyone’s patience holds hands and tries to cross the street together.

When spring returned, the judge made the guardianship final in the way these things get final—paper and stamps and a clerk who says “Congratulations” like a person at a graduation party. The trust continued to work the way James designed it to: boringly, beautifully. Bills paid on time. School fundraisers met. Baseball cleats replaced without drama. A savings account that grew one steady line at a time. It did not make news. It made a life.

One evening, late, after Lucas had fallen asleep with a library book on his chest and Sophia had texted a photo of a science project that did not explode, I took the envelope out again. I reread the part about contingencies. I traced the letters with a fingertip, the way you might touch a carving on a bench left in a park in someone’s name. I pressed the pages flat and felt, in my bones, the architecture of my son’s love—the beams and braces and angles that kept wind from taking the roof.

And it came to me, simple as the thought you have while washing dishes: James did not leave me power. He left me permission. To build. To steady. To choose the boring parts, again and again, until they added up to the kind of peace that never shows up in the glossy pages of anything and therefore is real.

On the night before the new school year, Lucas laid out his clothes on the chair by his bed: jeans, a striped shirt, socks with tiny baseballs. He pinned his flag to his backpack and set it upright so it could watch. He asked for a story and I told him one he knew: of a boy who learned to ride a bike in a tiny backyard, of a man who brought flowers on Wednesdays because midweek needed warmth, of a letter that held a future inside it like a room holds light.

He fell asleep smiling.

I turned off the lamp and walked to the table where the envelope rested, and I thought of Thomas’s first sentence to me in the chapel: immediate attention. He had meant the law. I heard the life.

I poured tea and actually drank it. I set out two bowls for breakfast, one for me and one for a boy who would put too much sugar on his cereal and then run back to the table to add cinnamon because he has learned there is always a way to make good things a little better. I looked out at the porch where the flag moved just enough to let me know the night had a pulse. I did not feel alone.

When people ask me how we managed it—how the house, the cars, the account, the plan—how any of it became something other than a fight—I tell them the truth. We didn’t manage it. We kept it. We kept faith with the person who wrote it down. We kept faith with the boy who needed both hands. We kept faith with the boring parts.

And the rest happened the way bridges happen: you cross them every day until one morning you realize you’re not thinking about falling anymore.

On a recent Wednesday, Lucas and I left the flower shop with a bouquet so orange it looked like October had spoken out of turn. At the corner, he paused and pointed. A small parade was forming—kids on bikes with streamers, a scout troop with a big flag, a marching band warming up with scales that sounded like a staircase about to become music. He tugged my sleeve.

“Can we follow?”

“We can lead,” I said, and we did, one block, then two, then the whole way to the park where someone had set up lemonade strong enough to wake the mayor.

Sophia joined us by the gazebo, out of breath and smiling real. We took a picture—Lucas in the middle, the chrysanthemums a blaze between us, the flag behind us unfurled and sure. Later, when Lucas fell asleep with grass in his socks and a program for the parade under his pillow, I looked at the photo and saw what the year had done to our faces.

We looked like people who knew where to stand.

That night I put the envelope back in its drawer. Not because I needed it less, but because I had learned to carry it in other ways—in habits, in calendars, in the patience to make room for someone else to arrive late and still be welcome, in the certainty that justice isn’t a showy thing in rooms with microphones, but a quiet thing in kitchens where a child finds his lunchbox exactly where it belongs.

And every Wednesday, we keep buying chrysanthemums.

Midweek still needs warmth.

Love still needs structure.

And a boy still needs both of his hands held, steady, until he can hold the world for himself.

Spring leaned into summer the year Lucas turned nine, and the house settled into a kind of music that made sense—shoes abandoned by the door, a whistle from the kettle, the thunk of a baseball against the fence as consistent as a heartbeat. I kept the trust records tidy and the fridge full, and we learned a new kind of quiet—one not born from caution, but from ease. The porch flag stirred in the evening breeze, and the neighborhood kept being itself: kids riding bikes in a loose pack, the mail carrier waving like clockwork, the distant hum of lawn mowers turning grass into neatness.

Sophia got better at arriving without hurry and leaving without smoke. She was still herself—she still enjoyed a good hotel lobby and a nice pair of sunglasses—but she began to bring different kinds of gifts: a math workbook Lucas actually liked, a list of free Saturdays marked “baseball rain delays,” a calendar reminder to bring cupcakes to the class party. She asked for the recipe to my chicken noodle soup and, a month later, brought over a pot that tasted like she’d learned the secret I never write down: give it time.

In early August, I sold one of the cars—a sleek thing James loved more for its engine than its shine—and folded the proceeds into Lucas’s education account. We kept the older, sturdier sedan because it had a trunk that swallowed baseball gear, folding chairs, groceries, and the odd school project shaped like a volcano. When I signed the bill of sale, I didn’t feel like I’d lost anything. It felt like a trade: horsepower for runway, shine for path. Later that night, I took out the folder, logged the deposit, and smiled at the steady slope of the line on the balance sheet. Boring, beautiful.

The last week before school, we painted Lucas’s room. He chose a blue with more gray in it than I expected, the color of Lake Erie on a good day with honest wind. We laid down drop cloths and wore old T-shirts and discovered that painting a room is half brushwork and half the decision to stop touching up the same corner. He taped a postcard over his desk—a field, a fence, a single tree—and wrote under it in careful print: practice is a place. I didn’t know where he’d heard it. I knew it was true.

He started fourth grade in sneakers that blinked once when he walked and a backpack with a flag pin that remained upright, stubborn as a Sunday morning. At curriculum night, Sophia and I took a photo with his teacher under a banner that said WELCOME BACK in letters cut from construction paper. We stood on the same side of the table again. It felt like we might keep doing that, not because someone ordered it, but because we’d chosen it and then chosen it again.

A week later, a letter arrived from the court. The judge’s clerk wrote that our reporting intervals could be extended based on “consistent compliance and observable cooperation.” It read like a dry thing. It felt like a standing ovation only we could hear. Thomas slid a copy into the folder, smoothed the page, and said, “Keep going.” He always says so little, and somehow it is always enough.

In September, Lucas’s team made the city championship. They played under lights while the air forgot it had been summer and learned, cheerfully, to be fall. He stood in left field with his knees bent, glove ready, and I watched him read the game the way you read a person you love—quietly, accurately, without turning it into a performance. He struck out in the second inning and did not kick dirt. He hit a clean single in the fourth and did not crow. Then, bottom of the sixth, two outs, runners on second and third, tie game—the kind of moment that turns the world smaller and sharper—he squared up and sent a line drive past third that walked in the win like it had been waiting politely for its cue. The coach lifted him off the ground and the team swarmed, small bodies bouncing like popcorn. He found me in the stands and lifted both hands, not for glory, but to ask if I’d seen it.

“I saw,” I mouthed. “I saw everything.”

We celebrated with ice cream that dripped faster than we could outrun it. Sophia met us at the shop, hair still in a low knot from work, eyes bright with the kind of pride that doesn’t tip over into ownership. She hugged him too long and then just long enough. He wriggled away and returned to his sundae. Life went on. The sundae was the point.

In October, we visited the law school for the Reynolds Scholarship reception. The dean introduced the first recipient: a young woman raised by her grandmother who planned to clerk at the county’s legal aid office after graduation. She spoke with the measured confidence of someone who had learned to choose her words and her hours. She said our last name, not like we owned the room, but like we’d built a small bridge across it. Thomas stood at the back and tilted his chin once at me, which, in the Bennetts’ private language, meant Good. This is good.

On the way out, we stopped by the bulletin board where students post flyers that live for two weeks and then curl at the corners. One of them advertised a panel on “Protecting Families With Planning, Not Fireworks.” I took a picture and sent it to Thomas. He texted back an emoji I didn’t know he knew how to use and then, of course, the words: Keep going.

The first snow fell on a Tuesday too early to be useful. School closed, work slowed, and the neighborhood huddled around its own fireplaces. Lucas and I made cookies that looked nothing like the photo and tasted exactly right. He wrote a letter to Santa, then crossed out Santa and wrote “Dear Future Me,” and listed three wishes: keep hitting, be kind, help Grandma. When he wasn’t looking, I folded it and slid it into the folder with the trust. Some documents grow a family just as well as any other.

When the court’s next review came due in January, the judge called us up and said fewer words than I’ve ever heard in that room. “Ms. Reynolds,” he said, “counselor. Ms. Ward. I have your reports. I have the school’s notes and the guardian ad litem’s observations. The arrangement stands. I won’t see you again unless you need me, which I hope you don’t. Keep doing what you’re doing.” He took off his glasses, rubbed the place they’d pressed, and added, “I mean it.”

We filed out with the ease of people leaving a matinee into bright winter afternoon light. In the hallway, Sophia touched my sleeve. “Thank you,” she said. Not for money. Not for winning. For the boring parts done well enough to be invisible. I nodded and touched her hand back. “We’re doing this,” I said, a sentence that surprised me by not sounding like a boast. It sounded like the truth.

The months found their steps. There was a field trip to the science center where Lucas declared the planetarium “good but too dark,” and an open house at school where he showed us his report on Ohio birds as if he’d discovered the state himself. There was one stomach bug, two lost mittens, three minor disagreements about bedtime, and the return of the orange chrysanthemums as soon as the shop could coax them out of the soil. On Wednesday evenings, we kept setting them in water by the window, and some weeks it felt like they kept us as much as we kept them.

In March, the refrigerator died with a gasp and a rattle. Ten years ago, that would have turned into an emergency with five loud opinions and a credit card bill no one wanted to look at. This time, it was a Tuesday task. I called a repairman who arrived with a silver toolbox and a Midwestern steadiness that could have leveled a house. He shook his head, we laughed about how machines pick their moments, and I bought a new refrigerator that did not chirp like a toy when you left the door open. I logged the expense under Household—Necessary and did not think about it again. The trust did what it was built to do: catch, cushion, continue.

By April, Sophia was seeing someone new. His name was Daniel and he spoke the way good men from small towns do—softly, with sentences that start farther back so they don’t step on anyone’s toes. He helped at the spring fundraiser without introducing himself to everyone first. He asked Lucas questions and remembered the answers. He carried chairs. He said goodnight the way a porch light turns on: steady, not showy. I watched, not with suspicion, but with the protective curiosity you keep for a child. And when it became clear that Daniel understood the difference between performing love and doing it, I exhaled a breath I didn’t know I’d been holding.

One Sunday afternoon, I found Lucas at the dining table with his homework. He had a sheet of lined paper and a pencil that had been sharpened within an inch of its life. “I have to write about a person who helped me,” he said, without looking up. “Is it okay if I put two?”

“You can put three if you’d like,” I said.

He wrote the names: Dad. Grandma. Mom.

He paused, mouth tilted to one side in that way that means the mind is trying on a thought to see if it fits. “I wish I could show Dad,” he said.

“You did,” I said. “You do. Every day.”

He nodded. He believes me more easily now. I think children hear how much we believe ourselves and tune to it like a radio station that comes in clear on the highway.

May arrived with its long light and field days and lists that felt like they never ended: sunscreen, water bottles, permission slips, a cake for the end-of-season picnic that needed to be “nut-free and safe and if possible fun.” We made a banner instead. Lucas wrote GO CARDINALS in letters so big they startled the trees. At the picnic, the coach gave him a certificate for “steady courage.” I didn’t know that was a category. I thought maybe it should be the only one.

On Memorial Day, the parade passed our block. The old veterans saluted and we saluted back. The high school band managed a march that looked like math and sounded like pride. A boy from Lucas’s class carried a small flag with both hands like he was holding the front door for the whole town. Sophia brought folding chairs and a blanket that kept sliding off our knees. Daniel bought three lemon ices and tilted his face to the sun like gratitude has a physical temperature. We waved at people we know, the way people do when they are lucky enough to keep living in the place that knows them back.

Sometime in June, after a thunderstorm that scoured the street and left the air smelling like a clean slate, I took the envelope out again. I do it less now, not because it matters less, but because its contents have moved into the walls, the calendar, the way the porch light clicks on when the sun hits a certain angle. I unfolded the pages and read the line that always steadies me.

Mom, protect the boring parts. They’re where all the love hides.

I set the pages down and walked through the house—the baseball glove by the door, the shoes that never quite make it to the rack, the worksheet on the table with the word “photosynthesis” written in a brave attempt at cursive. I opened the freezer and took out two popsicles. I handed one to Lucas and kept one for myself. We sat on the steps and watched the neighbor’s golden retriever attempt to befriend a squirrel who, mercifully, had other plans. Sophia texted to say she’d be five minutes late and then arrived exactly on time. Daniel waved from the sidewalk like he’d never learned to make an entrance and preferred it that way.

Late that night, after the dishwasher clicked and the house gave its small, secret sighs, I wrote a letter of my own. Not to the court or the bank, not even to Thomas, though I would tell him about it later in the week when we traded updates at the diner over eggs and the coffee that could strip paint. I wrote to the future—a future where a boy is a young man and a young man becomes the kind of adult who knows how to hold weight without turning it into a show.

Dear Lucas,

When you are ready, you can read all of your father’s letters. I hope you find in them what I did: a blueprint not for power, but for permission. You are allowed to build the life that holds you steady. You are allowed to be kind in boring ways. You are allowed to be loyal without being loud about it.

Here is what I know: Justice can feel like a big word in high-ceiling rooms, but most days it is small and local and looks like a lunch packed the night before, a hand held at the curb, a schedule kept because promises need places to live.

We have tried to keep those places warm for you.

Love,

Grandma

I folded the letter and placed it in the folder, behind the trust statements and the receipts and the letter James wrote in a hand that manages to be both lawyer and son. It felt like sliding a new beam into a structure that already stands on its own: you don’t need it today. You’ll be glad of it tomorrow.

In late July, we drove to the lake on a day so clear the horizon looked invented. We packed sandwiches that insisted on falling apart and a blanket that pretended to repel sand before becoming sand itself. Lucas ran to the water and ran back again, delivering shells like he’d been hired by the beach to inventory its shine. Sophia fell asleep for fifteen minutes in the kind of nap that can save a week. Daniel read a paperback with a rip in the cover and lent me his hat without asking if I was the kind of person who wears hats. I looked at them and saw not an arrangement, not a schedule, not a mediated compromise—but a family, particular and made and sufficient.

On the drive home, the air-conditioner sang a little and the radio found a station playing a song James used to hum when he thought no one could hear him. Lucas leaned his head against the window and mouthed the words. I reached over and turned the volume up one notch. We didn’t speak. We didn’t have to.

As summer tipped toward the long gold of early fall, the chrysanthemums came back in force. Orange, then deeper orange, then the shade that looks like the sun collapsed into petals. On a Wednesday that felt like a gift, the shopkeeper slipped an extra stem into our bouquet and said, “For your tradition.” I paid, and Lucas carried the flowers like a mission. At home, we set them in water and he stood back, hands on his hips, considering.

“Do you think Dad can see them?” he asked.

“I do,” I said.

“Do you think he likes that they’re orange?” he asked.

“I think he likes that we keep showing up,” I said.

He nodded. That answer, it seems, works for a lot of things.

One evening—after dinner, before homework, in the soft middle of the day where families improvise—I opened the front door and stood on the porch. The flag moved, slow and sure. The street held its ordinary light. Somewhere a radio played a baseball game in a backyard. I thought of the night I drove to Mercy Hospital down roads I chose to make longer because the short ones felt too sharp. I thought of the conference room with too much glass and not enough air. I thought of the courtroom and the quiet that followed a judge’s few good words. I thought of the envelope and its cargo, of Thomas’s steady counsel, of Sophia’s changing shape, of Daniel’s quiet, of a boy learning not just how to swing, but when to stand and wait and let the ball come into his strike zone.

The ending, people always ask for it—as if life arranges itself into a curtain call. Here it is, as honest as I can make it: Things don’t end. They proceed. And every day you pick up the thread you were handed and you do the next true thing with it.

We kept the house because James built it into the plan and the plan held. We sold what needed selling and kept what needed keeping. The trust did its humble work and will keep doing it, unglamorous and faithful. The court let us go because it knew we were already holding our line. Sophia found her feet and then her step. Daniel stayed in step without stomping. Lucas grew the way boys do when adults cooperate: taller by inches and steadier by miles.

On a Sunday afternoon near the end of summer, we grilled in the backyard while the neighbor’s retriever finally chose to befriend a butterfly instead of a squirrel. The table held simple food and more napkins than necessary. Lucas told a joke that made no sense and then made perfect sense. He asked for a second helping and then decided he’d had enough and offered it to Daniel, who accepted without fanfare. Sophia carried plates inside and brought them back out, clean and warm, because the dishwasher had finished and she liked the ritual of ending things tidy. I poured lemonade that wasn’t too tart this time. We ate. We talked. We watched the sky decide to be evening.

Later, when dishes had turned back into their places and the house began its night sounds, I pulled the envelope once more for the smallest look—just to touch the edge, to remind my fingers what stewardship feels like. Then I put it away. Not because it wasn’t needed. Because it had done its job, and because we had learned to do ours.

Every Wednesday we still buy chrysanthemums. We still set them by the window, where the light finds the color and makes a promise of it. Midweek still needs warmth. A child still needs both hands steady until he can steady his own days. Love still prefers structures to speeches. And justice, most of the time, still looks like a lunch packed on a Tuesday night, a calendar kept, a door held, a future paid for a little at a time, like a layaway plan with no grand reveal—only daily faith.

If you want a finale, here is mine: We did not get everything we wanted. We got what we needed and learned to treasure it. We did not vanquish a villain. We disciplined ourselves to be good, boring people in all the ways that keep a house standing. We did not announce our victory. We lived it—on porches, at ballfields, in courtrooms where the best outcomes are short and stamped. We carried on with the small, sturdy tasks that turn sorrow into shelter.

And when Lucas fell asleep that night—with the flag pin on his backpack upright as ever, with dirt under his nails from a game that mattered only to those who were there, with a future that looked less like a cliff and more like a trail—light from the hall traced his freckles and he smiled the way children do when their bodies are telling them a true story: You are safe. You are loved. You will wake up where you belong.

Tomorrow we will buy the flowers again.

We will keep going.

News

November 2nd, 1944. 3:47 p.m., somewhere over Czechoslovakia—and Lieutenant Bruce Carr watches the oil pressure needle fall to nothing as black smoke curls past the canopy of his P-51 Mustang.

November 2nd, 1944. 3:47 p.m. Somewhere over Czechoslovakia, Lieutenant Bruce Carr watches the oil pressure gauge drop to zero. Black…

One pilot in a p-40 named “lulu bell” versus sixty-four enemy aircraft—december 13, 1943, over assam.

At 9:27 a.m. on December 13th, 1943, Second Lieutenant Philip Adair pulled his Curtiss P-40N Warhawk into a climbing turn…

0900, Feb 26, 1945—on the western slope of Hill 382 on Iwo Jima, PFC Douglas Jacobson, 19, watches the bazooka team drop under a Japanese 20 mm gun that has his company pinned. In black volcanic ash, he grabs the launcher built for two men, slings a bag of rockets, and sprints across open ground with nowhere to hide. He gets one rise, one aim—then the whole battle holds its breath.

This is a historical account of the Battle of Iwo Jima (World War II), told in narrative form and intentionally…

At 0700 on October 4th, 1943, Colonel Hubert Zmpy stood on the hard stand at RAF Hailworth and watched mechanics fuel 52 Republic P-47 Thunderbolts for a bomber escort run deep into Germany.

Just after dawn on October 4th, 1943, Colonel Hubert Zemke stood on the hardstand at RAF Halesworth and watched mechanics…

THE DAY A U.S. BATTLESHIP FIRED BEYOND THE HORIZON — February 17, 1944. Truk Lagoon is choking under smoke and heat, and the Pacific looks almost calm from a distance—until you realize how many ships are burning behind that haze.

February 17, 1944. The lagoon at Truk burns under a tropical sky turned black with smoke. On the bridge of…

A B-17 named Mispa went over Budapest—then the sky took the cockpit and left the crew a choice no one trains for

On the morning of July 14, 1944, First Lieutenant Evald Swanson sat in the cockpit of a B-17G Flying Fortress…

End of content

No more pages to load