I didn’t keep the note because it was clever. I kept it because it saved my life.

It lives in a small wooden box on my dresser, tucked between a postcard from Yellowstone and a blue ribbon from Sarah’s eighth-grade science fair—five inked words, slanted and urgent, that rerouted our future: Pretend to be sick and leave.

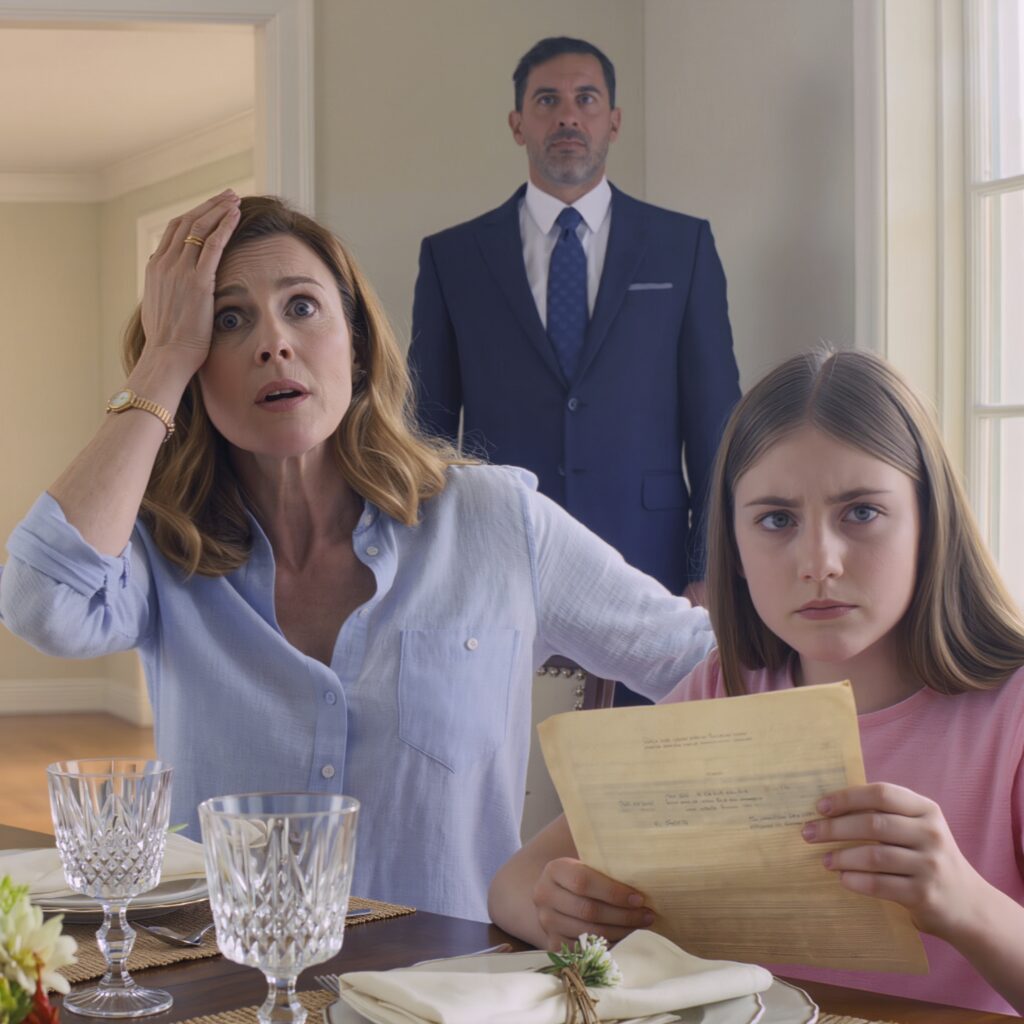

If I’m honest, I almost didn’t listen. It was a Saturday like any other on the outskirts of Chicago—the kind with a light wind that lifts porch flags and the smell of coffee moving through a house that’s been scrubbed within an inch of its life. The dining room table was set the way magazines set tables—ironstone, linen, three vases of grocery-store tulips that looked more expensive than they were. Richard—my husband of two years, my second chance at a solid middle—had invited his partners for brunch to talk “expansion.” He wore cufflinks and a smile you could bounce a quarter off. I wore the dress Sarah once said made me look like I ran a bookshop that smelled like vanilla and ink. It should have been an ordinary good day.

But Sarah, fourteen and quiet as snowfall, slid that note across the kitchen counter like someone defusing a wire. Her hands trembled. Her eyes did not.

I followed her to her room. I read the words twice. Richard’s knock sounded like a cue in a play. I told him I had a migraine. We left. Ten minutes later—parked behind a hardware store with a delivery truck idling nearby and a small flag on a short pole snapping in the breeze—Sarah told me why.

He was going to do it with tea, she said. Because I always drink tea when we host. Because it looks polite and photographs nicely. Because a mild “episode” would read as stress to a room full of colleagues. Because a timeline had been written in a hand I knew too well: 10:30 Guests arrive. 11:45 Serve tea. Effects in 15–20 min. Look concerned. Call ambulance at 12:10. Too late.

Her words closed a fist around my ribs. I wanted to deny it with my whole body. I wanted to fix this with reasonable explanations, to say that I knew this man and this house and my own judgment. But the receipt she showed me was real. The notebook she opened—a sturdy little thing with graph paper and color-coded tabs—was real. The photos she’d taken of an unlabeled amber bottle in his desk were real. The calls on a second phone bill to a number saved only as “Santos” were very real.

Fear is fast. But so is anger, once it stands up.

We went back.

People imagine courage as a trumpet blast, but sometimes it’s an apology in the right register at the right moment. We returned to the house and apologized—me for the “headache,” Sarah for looking pale. I saw the flicker behind Richard’s eyes when I declined a cup of the tea he described as “a new blend that helps with migraines.” I felt the heat of his hand on my back as he steered me through our guests, introducing me like I was a product that had arrived on time and under budget. I watched Sarah disappear down the hall like a shadow that knows where it’s going.

The text came twenty minutes later: Now.

I excused myself with a smile that didn’t touch my teeth and climbed the stairs too fast for someone who supposedly hurt. We nearly ran into Richard in the hallway. He was calm in a way I’ve since learned to fear, the calm of a man who believes he is smarter than the room. He asked gentle questions. He suggested tea again. He locked the door behind him when he left.

Fear is fast. Mothers are faster.

We made a rope from the comforter, tied it to the desk’s iron base, and went out the window into a thin November sun. I landed badly and felt something tear in my ankle. Richard shouted my name with a voice that finally matched the thing I couldn’t name. We ran until running was just wanting to live. We crossed the community path where cyclists nod at you like a covenant and cut through the nature preserve to the metal service gate that opens with a keycard and a prayer. The green light blinked yes. We found a taxi at the curb like it was any other errand day and went to Crest View Mall, where a thousand ordinary Saturdays swallow anything unusual whole.

We chose the coffee shop near the back because the tables are spaced and the barista has a voice like a librarian. I called the only person I could think of who lives in facts the way surgeons live in anatomy: Francesca Navaro, a friend from college who had turned late nights reading case law into a life as a criminal defense attorney. She said three things: Don’t go home. Don’t talk to the police without me. Send everything.

While we waited, my phone vibrated—a flood of texts from Richard, each one a neat tile in a narrative mosaic: Where are you? People are asking. Baby, you scared me. Please come home. If this is about yesterday, let’s talk. I love you. He told me the police had been notified; officers were en route. He wrote about blood in Sarah’s room, as if read from a script we had not rehearsed.

The officers arrived first. They were polite the way bank tellers are polite—formal and trained and faintly weary. They said Richard feared I was in an “altered state” and that the minor might be in danger. Sarah spoke crisply, like she was testifying in a televised civics class. She showed them photos on her phone. A bottle. A page of notes. The name Santos. They didn’t dismiss us; they simply didn’t know what to weigh.

Then Francesca walked in wearing a navy suit that meant business and a look that meant we’d borrowed time and she intended to pay it back in full. She identified herself as counsel and moved us, in language and posture, from two distressed females to two citizens alleging a crime. She used words I’ve since heard in passionate noon-hour speeches—credible threat, documentary evidence, timeline, motive. The officers asked us to come to the precinct. Francesca agreed and got us there fast.

That afternoon unspooled like a complicated rope. Evidence technicians left for our house. A lieutenant with a thick notebook took our statements separately, then together. We submitted Sarah’s photos. We handed over her notebook, which made me want to both sob and applaud. I consented to a toxicology screen. I texted Richard a single sentence—We are with the police—because Francesca said it was smart to look transparent even when you were utterly opaque with fear.

Richard arrived at the precinct with the face he wears for funerals and charity galas—concern playing softly across features meant for cameras. He called me “honey” and “sweetheart” with a tremor calibrated for sympathy. He told the commander I’d been struggling with “nerves” and “sleep issues” and that a “Dr. Santos” had recommended something to take the edge off during “big days.” He described—calmly, credibly—the idea of brewing a gentle tea with a few drops of a mild tonic that a lot of people use, nothing dangerous, nothing more than you’d find in a vitamin aisle.

Facts came in like crosswinds. The amber bottle, recovered from the desk, tested preliminary positive for compounds that do not belong in a human body in any dose. The “tea” in the kitchen—untouched, cooling—held the same signature. The blood in Sarah’s room was type O; neither of us is. Richard is. The timeline page bore indentations consistent with the shopping list in our kitchen junk drawer, a match you can see when rubbed with soft graphite. The calls to “Santos” traced to a prepaid number bought in cash three towns over.

The moment he lunged at me will play in slow motion in my head for the rest of my days—not because he reached me (officers are trained and fast) but because his face dropped the mask so cleanly it was like watching a portrait be repainted with one swipe. There was no love in that face. There was calculation and fury and a hollow where a center should be. The cuffs went on with a sound that felt like the first true punctuation of the day.

The charges were not simple, because nothing that wears a suit and walks into your house is simple. Attempted homicide. Fraud. Evidence tampering. Later, something darker, when a neighboring county reopened a file about a widow who’d married a charming man and died quietly in a rented home, mourned mostly by his bank account. But that was to come.

The next months were made of lists and grocery runs, depositions and deli counters. I learned that cases do not move at the speed of fear; they move at the speed of paper. I went back to work at the community college two weeks after everything broke—not because I’m brave but because I needed to be somewhere with fluorescent lights and planners and the normalcy of student emails that say, “Sorry, I forgot the attachment.” The night news sometimes mentioned my name as if I were a character on a show. I changed our locks and our routines. Sarah slept with the lamp on and, when she finally turned it off, slept like someone who had earned it.

Francesca built, and I watched her build. She pulled records on Richard’s company and found a slope disguised as a plateau. She subpoenaed bank statements that tracked little transfer footprints from our shared account to a solo one that existed under a benign name—something like JRS Holdings, the kind of name no one looks at twice. She mapped a pattern in trips he took, a sameness in the hotels and rental cars, a constellation that only looked random if you didn’t know what shapes to search for. She hired a forensic toxicologist with hair the color of steel who explained things in words I could understand and then in words a jury would, too. She brought in a private investigator, James Rodriguez, who spoke quietly and carried a notebook, the rare sort of man who notices the second trash pickup on Thursdays and understands what that means for a neighbor’s routine.

James found the storage unit. He found the box of papers that answered questions we hadn’t known to ask: old statements, overlapping signatures, two driver’s licenses with the kind of differences you’d only spot if you’d trained your eyes to spot them. He found, pinned to a corkboard inside the unit, a flier from a health fair where Richard had volunteered once, as if altruism were a costume he could borrow. The flier had a phone number circled—the same burner tied to “Santos.”

I did not weather these months gracefully. I woke in the night to check the front door three times. I sometimes stood in the kitchen with my hand on the pantry door like I might find the right future on the other side. I snapped at Sarah about dishes and then apologized with my whole heart. I cried in the car where she couldn’t hear. I did not see romance in any of this. I saw survival, which is less pretty and more necessary.

Pretrial hearings became a parade of measured voices and page numbers. Richard pled not guilty with the calm of a man who expects good luck to keep doing what it’s always done for him. He hired counsel whose ties cost more than my monthly rent in grad school. He smiled for cameras leaving court, standing one step behind his attorney the way people stand one step behind prizes.

Trial did not arrive like a thunderclap; it arrived like winter, the slow accumulation you only fully register when you notice the white piled high on the sidewalk.

That first day, I wore navy because Francesca said juries trust navy. Sarah wore a sweater the color of late sunlight and held my hand under the table until her fingers warmed mine. The courtroom had the solemn smell of wood and paper and the cold undertone of a building whose windows don’t open. The judge looked like a grandfather and sounded like a metronome. The prosecutor was a woman with a voice like clear water—steady, reflective, cutting when it needed to be. Richard sat at his table with a legal pad and two pens aligned precisely like runway lights.

If you have never testified about the worst day of your life, I hope you never have to. If you do, I hope you have a lawyer like Francesca who asks the most difficult question in a way that lets you climb over it. I spoke into a microphone that made my own breath sound too loud. I told a room of strangers how my daughter saved me. I learned that a courtroom records not just words but pauses.

Sarah testified with the kind of poise that made the court reporter glance up. She did not dramatize. She did not tremble. She told them what she heard and what she did. When the defense tried to press the idea of a teenager misreading a whisper, she gave him a look that said she’d sat in enough classrooms to know when an adult was playing a trick with language. When they hinted at a “difficult stepfamily transition,” the prosecutor slid a photograph onto the screen of the note Sarah had written—five words that made the gallery shift in their seats almost in unison.

The toxicologist did not sensationalize. He talked about compounds and metabolism, about dosage and windows of effect. He explained how a timeline written by a man in a house can match a timeline written by chemistry in a body, each minute a rung on a shared ladder. He described how a kitchen kettle can be turned into a tool if you strip it of love and leave only intention.

The defense tried to introduce doubt with the soft hands of people who have used soft hands to win before. They suggested a mislabeling. They suggested a panicked assumption. They suggested that I had told myself a story because stories are easier to carry than chaos. They did not suggest why a note in my own daughter’s hand would exist in a world where I’d imagined a cozy lie.

In the three weeks of testimony, there were days I watched the jury more than the witness. Jurors look like America looks at the grocery store and on commuter trains—cardigans and flannel, a tie on a day when the weather bites, a woman who keeps mints in her bag and passes them down the row. I saw them listen hard. I saw their eyes on Sarah when she talked about the night in the hallway. I saw their faces when the lab analyst read the concentrations in the cup set on our kitchen counter with the good linen under it.

When the verdict came, it came like the end of a held breath. Guilty, the foreperson said, on the principal count and on the charges that nested beneath it. The sentence—thirty years for what he did and another fifteen for what he stole—landed like the sound of a heavy door finally shutting. In the weeks that followed, investigators reopened the file on the widow and found what they hadn’t thought to test before. Her family sat two rows behind me the day the new charges were added. We didn’t speak. We didn’t need to.

Justice did not give me back the two years I spent believing a story that wasn’t true, but it did something I didn’t expect: it made room for us to write a better one.

We sold the house. I thought I would cry when we left, but I did not. A place can be lovely and wrong; you can love the light on the hardwood and still want a new address more than you want air. We moved to a third-floor apartment on a quiet street with a swing set in the courtyard and a view of the kind of small American flags that live on porches without speechifying. The first night, we ate pizza on the floor off paper plates and passed the sparkling water like it was champagne. The last box we opened was the one marked BOOKS & PROOF. I slid the wooden box onto my dresser. When I closed the drawer, I felt something in my chest settle into a position it hadn’t found in months.

Francesca became the friend you text pictures of sunsets to. One Friday, she knocked on our door holding takeout and a bottle of something celebratory I couldn’t pronounce. She carried news, and for once, it was good. The court had approved restitution from the sale of Richard’s assets; the number was larger than I had let myself imagine. “Start a scholarship,” she said. “Replace your retirement. Fix whatever needs fixing.” We did something smaller and stranger first: we slept in. The kind of sleep that means your nervous system finally believes you.

I kept my job. I love work that is ordinary and useful. I love students who say, “Hey, I finally got it,” about a paragraph that behaved for them after three tries. I love the whiteboard and the marker smell and the calendar with little red circles around holiday weekends. Ordinary feels like luxury once you’ve lived in the opposite.

Sarah started high school looking like a girl in a movie where the script finally understands her. She joined debate and a club that builds little robots that carry ping-pong balls from one side of a room to the other. She planted an herb box on the balcony and taught herself to make lemon pasta on Tuesdays. Therapy helped, not because it erased anything but because it gave us words for it. We learned to say panic without whispering. We learned that love and vigilance can share a bed.

We started new rituals. Saturday mornings, we walk the farmers market where the produce comes with opinions and the pastries disappear by 10 a.m. We say hi to the same golden retriever each week like he’s a neighbor. We stop at the table where they register voters and sign the clipboard with that small satisfaction Americans feel when participating in a thing bigger than themselves. On the Fourth of July, we watched fireworks from the roof with plastic cups of lemonade, shoulder to shoulder with strangers whose oohs and ahhs sounded exactly like hope.

Richard’s first wife’s family invited us to her memorial when the case concluded. It was held under a canopy behind a brick church in a town that looks like a quilt—red rooftops and green lawns and a sky the color of laundry. I brought flowers. We listened to stories about a woman I never met but would think of often after that—her laugh, her casseroles, the way she answered the phone on the second ring saying hello like a song. When they said her name, people cried in a way that washes rather than drowns. Justice had arrived late, but it had not missed its turn.

On the one-year anniversary of the day everything broke, we set our small dining table with the white plates and the tulips I still buy because they remind me that effort can look like grace. Francesca came, and so did our neighbor who waters plants when we travel, and two of my colleagues who know the exact right stories to tell after dinner. I made the lemon pasta because Sarah insists it’s good luck. We opened a bottle with a ridiculous cork. We toasted the kinds of things people should toast more often: to ordinary Saturdays, to teenagers who trust their instincts, to lawyers who do not blink, to the virtue of paper trails, to the gift of seeing people as they are, not as you wish them to be.

After everyone left, I stood at the sink with my hands in soapy water and looked at the note sitting on the counter where I’d set it for the evening—Pretend to be sick and leave—framed in the little stand we usually use for recipes. I don’t display it often; it is not art. But tonight it felt right to let it sit in the open like a small flag planted on good ground. Sarah came up behind me and bumped my hip with hers in the way she does when words feel unnecessary.

“You kept us,” I said, and she gave me a look that I will find in my bones when I am very old.

We started a scholarship in the name of a woman who loved second-ring hellos. One student each year—someone who wants to study something steady and useful—gets a check and a letter from us that says, in a thousand nicer words, Go make a life that’s yours. We funded it with a portion of money that once felt like a future stolen and now feels like a future redirected. The first recipient wrote back in handwriting so round you could rest in it. She said she’d buy textbooks without asking her mother which bill to skip. I tacked her note to our corkboard with a pin shaped like a star.

Sometimes people ask why I didn’t see it sooner. The answer is that I did, but love can be a house with rooms you avoid. You tell yourself you like the front porch enough to ignore the basement smell. You polish the banister and learn to turn the lights on before you enter. Then one day your daughter writes five words on a scrap of paper and hands you the keys to the only door that matters: out.

I am not naive. I know life will not forever be as gentle as a balcony herb box and a debate tournament and a stack of student essays with two exceptionally promising metaphors. But I also know this: we are better now. Not happier in a postcard sense, but stronger in the way bridges are strong—steel hidden under paint, math under beauty, the practiced flex that makes you feel safe when you cross.

In the spring that followed, James—who had kept in touch in the quiet, professional way good people do—stopped by with a thin cardboard box. “Records release,” he said, smiling like a man who knows the difference between vengeance and verification. Inside were copies of letters Richard had sent to an insurer, the phrasing careful, the timing telling. We didn’t need them anymore to prove anything. But seeing the paper trail stacked and labeled felt like closing a drawer that had been stuck a long time.

That summer, Sarah and I drove a rented Corolla through a net of small towns with names that sound like front porches. We ate pie at a diner with fifty-year-old stools. We parked at a rest stop where a state flag flapped itself silly in the prairie wind. We learned to read the sky for rain. We invented a game where we guessed what each house we passed would smell like—lemon oil, cinnamon, laundry—and were right more often than you’d think. On a Thursday near dusk, we pulled off for a high school marching band rehearsal because the tubas looked like moons and the field lights hummed like welcome. A girl in a blue T-shirt lifted a flag and caught it clean, and the whole world felt briefly, beautifully aligned.

A few weeks after we returned, a letter from the college with the brick library arrived with a particular thickness that made my knees weak for good reasons. Sarah read it out loud in the kitchen, voice breaking on the words “we are pleased.” She laughed and cried at the same time, the exact sound you hope a future makes when it walks into a room. We celebrated at the corner restaurant where the waitress calls you honey no matter how old you are and the vinyl booths sigh when you sit. We ordered pie before dinner because we could.

In the fall, we packed a car with boxes labeled DORM in handwriting so big it nearly counted as art. We drove past water towers and a billboard that promised the best barbecue north of Nashville. On move-in day, we climbed the stairs with crates of books and a corkboard and a plant in a white pot that looked resolved to thrive. Her roommate’s parents had the same stunned, proud expressions we did. I slid a note into Sarah’s top drawer—a new one, in my hand this time: I trust you. You saved us. Call me for everything, including nothing.

Thanksgiving came around again, as it does no matter what we live through. We set a table not to prove anything, but to belong to ourselves. Francesca brought sweet potatoes; James—unexpectedly shy outside his work—brought rolls from a bakery that sells out by noon. Our neighbor contributed a green bean casserole with crunchy topping that made Sarah close her eyes in appreciation. We went around and said what people say, but this year it rang like a bell that had been polished back to bright: for a system that worked when we needed it; for the stubbornness of teenagers; for the grace of ordinary days.

Months later, at the Saturday market, I met a man in the line for peaches. He wore a ball cap and patience, and when the old farmer moved slowly to weigh each bag, he didn’t sigh or check his watch. We talked about nothing in that easy way strangers do when the sun is kind. His name is Daniel. He listens more than he speaks, carries groceries without announcing that he is helpful, and understands that trust is built like a house—one measured board, one true nail, level checked and rechecked in the light. We are careful and simple with each other. He asks about Sarah first. He knows the story, all of it, and doesn’t try to edit it down to a line.

We took it slow in a manner that would bore gossip and delight a therapist. Walks by the lake. Church rummage sales where we bought a casserole dish because the price was ridiculous and the shade of blue made us laugh. Ball games on a radio because sometimes you want the cadence without the screen. He came to Sunday dinner and brought a store-bought pie with an apology that sounded like respect—for the table, for us, for the long road that made us slow.

On the second Christmas after the verdict, he asked if I’d like to go see the lights on Maple Street, where the neighbors do too much on purpose and it somehow works. We walked past porches beaded with icicles of LEDs and wreaths as wide as a door. He stopped under a maple branch that held one stubborn leaf as if the wind had asked it a question and it hadn’t decided yet. He did not kneel. He did not speechify. He said, “I want to be where you and Sarah are, in the ways that help.” I said yes because the relief in my chest felt like a bell rung correctly. We married in the spring at the park district pavilion with a sheet cake and a punch bowl and the kind of music that lets shy people dance.

Richard is where the state keeps men who mistake calculation for brilliance and other people’s lives for lottery tickets. He writes letters sometimes that I do not read. His appeals travel their slow, predictable routes. The past is a country I visit only with a guide now, and her name is perspective.

Sometimes, late at night, I walk to the kitchen and stand at the sink with the light over the stove casting a small golden circle like a stage in a dark theater. I fill the kettle and set it on the burner and watch for the first ghost of steam. It’s a ritual I almost gave up. But rituals do not belong to the people who tried to ruin them. I brew chamomile with a slice of lemon and set the cup on the counter like a peace treaty I write with my own hand. Sarah wanders in and steals a sip and says, “Too hot,” and then steals another. We watch the night lights of the courtyard blink and breathe and drift toward bed.

When people ask what saved me, I tell them the truth, which is simple and hard: a note, a girl, a decision. And then the long work of friends who show up and systems that, against the odds and on the right day with the right people, can still choose the right side.

Our story does not end with a door slamming or violins. It ends with dinner on the table and the balcony door open to let the evening in, with the mail stacked neatly and the scholarship letter pinned to the corkboard and the ordinary bravery of tomorrow waiting on its hanger. It ends with Christmas lights looped along the balcony railing and a cardboard box of ornaments we’re building anew, with a tiny one shaped like a kettle that Sarah insisted we buy because “we get to choose what things mean.” It ends with me closing the wooden box that holds five hurried words and everything they purchased for us, turning out the kitchen light, and walking down the hall to a home that bends toward morning—because justice did not forget us, because love learned to tell the difference, because a girl wrote a sentence and a mother believed her in time, and because, in this country where porch flags lift in evening breezes and neighbors bring casseroles that crunch, there are still days when the right thing happens at the right table, and you get to stay to taste it.

Daniel and I were married on a mild Saturday in May, the kind of Midwestern day that smells faintly of cut grass and rain that changed its mind. We said our vows under the park district pavilion while the ducks made diplomatic circuits of the pond and the band from a nearby Little League game floated over the hill in bright, off-key bursts. There were folding chairs, paper cones of butter mints, and a sheet cake with the frosting slightly smudged where the bakery box had bumped my elbow. No chandeliers, no fireworks, no theatrical gestures—just the clean feeling of a promise made in daylight with witnesses who know how hard-won an ordinary joy can be.

Sarah tucked wildflowers into mason jars along the picnic tables and made a toast that sounded like a letter she would write to herself someday: brief, precise, tender. James pretended not to dab his eyes; Francesca didn’t bother pretending. I wore a blue dress that matched the sky when a breeze skims it, and Daniel wore the suit he’d bought the year his father retired—a little loose in the shoulders, as if he needed room to grow into the next good version of himself. When we drove away, the tinny ring of can lids our friends had tied to the bumper trailed behind us like punctuation marks. We didn’t head to an airport or a beach. We checked into a small inn by the lake forty minutes from home, where an elderly clerk slid us a brass key and said, “You don’t need the Wi-Fi password. Trust me.” He was right. We didn’t.

Summer moved in and put its elbows on our windowsills. Sarah packed for college, then repacked, then declared that no human being should be expected to compress a life into three plastic bins. We solved it by buying a fourth. On move-in day, the campus green looked like a well-organized emergency—minivans open like clamshells, parents distributing mini fridges like aid workers, roommates approaching each other with the formal caution of ambassadors. We lofted a bed, negotiated a poster’s position by fractions of inches, and met an RA who could project her name to the far end of the hall without shouting. When it was time to go, I slid a note into Sarah’s palm: I trust you. You saved us. Call me for everything, including nothing. She slipped it into the corner of her mirror. Then she squared her shoulders and walked us to the elevator with the smile of someone drafting herself in real time.

Back home, the apartment felt both too quiet and perfectly measured, like a room after the orchestra has tuned but before the conductor raises a hand. Daniel and I found a new rhythm without speaking much about it: two mugs, one kettle; his jacket on the chair by the door; my grading on the end of the couch; a shared grocery list on the fridge held up by a magnet shaped like a tiny American flag we found in a box of thrift-store knickknacks. On Saturdays, we haunted estate sales not for treasure but for the small stories objects tell—a chipped porcelain cow creamer, a stack of recipe cards in a tidy hand, a photo of a family lined up in front of a station wagon with optimism to spare. We took those modest relics home and let them cheerfully populate our shelves, ordinary ambassadors from other lives.

If the past visited, it did so at respectable hours, no longer pounding at 3 a.m. The appeals came and went like distant trains; Francesca texted updates as if she were tracking weather systems, calm and factual. “Affirmed,” she wrote once, then again months later. “Denied,” she wrote another time, a small word that lifted an invisible weight. The scholarship fund grew, slowly at first, then faster, because good ideas have a way of finding allies. We named it for the first wife—the woman whose second-ring hello had become a compass for me—and every spring we stood at a podium in the community college auditorium and said her name out loud. The recipients spoke about radiography programs and welding certifications and early childhood education, about work that supports and builds and heals. Each one wrote us later, not with grand declarations but with sentences that hummed with relief: “I didn’t have to choose between gas and lab fees.” “My mom cried when I told her.” “I will pay this forward.”

James, who never lost his investigator’s habit of noticing the periphery, started volunteering with a group that teaches seniors how to avoid scams. He asked me to join one Saturday at the library. I expected a handful of people and a folding table with brochures. The room was full—cardigans, baseball caps, a man in suspenders who took notes as if he were auditing a graduate seminar. I talked about paper trails and second opinions and how to recognize the difference between urgency and pressure. I said the words that had saved me—trust your instinct—and watched them land. A woman with a purple cane raised her hand and asked, “What if the person you need to trust is yourself, and you’ve been trained for years not to?” I told her the truth: you practice. You say “No, thank you” in the mirror until your mouth knows how. You write down what happened the way a scientist would. You tell someone you trust and let them stand next to you while you make the next call. Afterward, the man in suspenders pressed a grocery store gift card into my hand and said, “For the scholarship. It isn’t much.” It was plenty.

Autumn walked in on a gust of clean air and turned the maples into loud whispers. We hosted a small potluck for neighbors and realized, with something like wonder, how quickly a hallway nod can become a habit of care. The woman from 3B brought a sweet cornbread that tasted like sunlight; the quiet guy from 2A surprised everyone with deviled eggs so balanced they started small arguments about paprika. Someone set a portable speaker in the window and an old Sam Cooke song lilted out into the courtyard. A kid learned to ride a bike between our patio chairs. A small dog wearing a bandanna supervised. I remember thinking, not dramatically but with quiet conviction: this is the life I hoped existed, even when I couldn’t see it.

Thanksgiving that year was big the way a heart is big—stretchy, ready. Sarah came home with a basket of laundry and a human confidence that had found its setting. She told stories about professors and 8 a.m. labs and the sacred geography of coffee on campus. Daniel taught her to carve the turkey by guiding her hand with his, a gesture as untheatrical as it was tender. We went around the table naming gratitudes—not as inventory but as practice. I said I was grateful for second chances that arrive dressed as quiet men with patient eyes. Sarah said she was grateful for a mother who listens. Daniel said he was grateful for a table where stories don’t need to be edited to be welcome. Francesca raised her glass and said, “To receipts, in every sense,” which made us laugh and also nod, because yes.

Winter laid down its deliberate whiteness. We strung lights along the balcony railing, all warm bulbs and sensible distance, like a constellation that knew not to crowd. We bought a small tree that smelled like memory and hung a modest jumble of ornaments: a paper snowflake, a wooden star, the tiny kettle Sarah insisted we buy because, in her words, “we get to choose what things mean.” On Christmas Eve, we went to the late service at the little church that keeps its doors unlocked for anyone who needs to sit down and think. The hymn lyrics lived in my mouth without effort. Peace, the old carol proclaimed, good will. I found myself believing these were not just seasonal words but tools, as useful and blunt as a wrench.

January returned us to what I’ve come to love best: schedule and repetition, the classroom and the kettle, the market and the mail. Daniel’s grown children—polite, curious, carrying their father’s gentleness like a shared inheritance—came for Sunday dinner and stayed long after the plates were washed, talking about tax forms and old baseball cards and how to measure a life. We did not hurry to blend; we learned to overlap. One night, his daughter asked if she could call me by my first name until something else felt right. Yes, I said. The next time, she called me Helen and stayed to help put away the leftovers, which is a love language as sturdy as any.

Spring tiptoed back with its unsinkable optimism. When the thaw came, the courtyard unfurled as if on cue—chalk drawings, wind chimes, plastic Adirondack chairs taking their posts. The cardinal returned to scold us sweetly from the railing. I planted basil, mint, and the kind of tomato that tries to become a tree if you don’t negotiate with it. Daniel built a trellis using instructions he claimed were “mostly instinct” and I claimed were “mostly YouTube,” and somewhere between our claims the tomatoes agreed to cooperate.

In April, we attended the dedication of a new lab at the community college, a space our scholarship helped finish—modest, immaculate, real. The dean, a precise woman whose laugh always surprised me, spoke about public good and private generosity, about what happens when people who could mind their own business decide not to. A plaque on the wall bore the name of the first wife and a sentence Sarah had written as the fund’s unofficial motto: “We take care, and we keep receipts.” The students applauded like a pep band that meant it.

That night, we sat on the balcony with bowls of ice cream and watched the sky trade blue for violet. Across the courtyard, a small flag on someone’s stoop lifted twice in a breeze and then rested, as if nodding. I thought of the long chain of hands and hours that had carried us here—Francesca’s briefs, James’s quiet questions, a forensics tech’s careful pipette, a juror’s steady attention, a clerk’s stamped form, a judge’s patient throat-clearing. How many ordinary people had chosen to do their exact job well on the days our lives needed them? The answer felt like a chorus singing offstage.

Sarah called from campus to tell us she’d been accepted into a summer research program. “It’s nothing glamorous,” she said, delighted anyway. “We’ll be testing water samples and building a data set nobody except city planners will ever read.” Exactly, I said. Build the world where it doesn’t show, where it matters most. She paused and added, softer, “Mom, I know what I want to do.” She told me, and it was work that would fix things people don’t see until they break. It fit her like a promise.

On the second anniversary of the day she handed me the note, we did not make a speech or stage a ritual. We went to the diner with the good pie and sat in a corner booth that knows us now. We split a slice of cherry and a slice of apple because life is too short to pick. Daniel stole the last bite of mine and I pretended to be offended. On the way out, the waitress pressed a paper bag into my hand. “For home,” she said. Inside were two biscuits wrapped in wax paper and a smiley face drawn in black marker like a benediction.

And then—because the best endings are not doors but porches—we stayed. We kept watering the basil. We kept showing up at the library workshops. We kept writing checks to the scholarship fund and notes to the students we’d never meet. We kept setting the table for whoever was hungry or lonely or curious or all three. We kept watching the news with the volume at a level that informed without consuming. We kept voting in small elections that determine whether the crosswalks are painted bright and the firehouse has what it needs. We kept hanging our coats by the door and tucking another blanket into the basket by the couch and calling each other home for dinner.

Sometimes, when I pass the wooden box on my dresser, I open it and look at the paper—not to relive a terror but to honor a choice. The ink has softened; the folds are wearing thin; the words are still as clear as the day a girl with a spine of steel wrote them in a rush: Pretend to be sick and leave. That sentence once ushered us out. Now it invites us in—into rooms we built with steadier hands, into days arranged not by fear but by affection and purpose.

Justice did what it could and then stepped back, as justice should, leaving us to do the rest. Love—quiet, competent, unshowy—did the daily lifting. And hope? Hope is the kettle singing at night and the porch flags moving in the evening air, the band striking up on a high school field at dusk, the clerk who says “Affirmed,” the student who buys her textbook new, the neighbor who knocks because he made too much chili, the daughter who calls to say the train is late but she’s on her way.

Our story keeps ending the way good stories do: not with a cliff but with a horizon. Some evenings, I take my tea to the balcony and watch the light slip into the tidy geometry of windows across the courtyard, each square a small theater of someone else’s ordinary. Daniel reads the paper. Sarah’s text tone pings: a photo of a lab bench, a joke about statistics, a selfie with a friend holding mugs the size of soup bowls. I lift my cup to the air and say, simply, “Yes.” And if there’s a flag to be seen in the corner of my eye, if there’s a line of laundry on someone’s porch, if there’s a dog sighing on a mat and a kid practicing free throws after dinner—so much the better. This is the country we make on our blocks and in our kitchens, official only in the ways that count: receipts kept, doors unlocked for the right knocks, justice on paper and in practice, love measured out in helpings you can taste.

That is our ending. That is our afterward. That is how we live.

News

November 2nd, 1944. 3:47 p.m., somewhere over Czechoslovakia—and Lieutenant Bruce Carr watches the oil pressure needle fall to nothing as black smoke curls past the canopy of his P-51 Mustang.

November 2nd, 1944. 3:47 p.m. Somewhere over Czechoslovakia, Lieutenant Bruce Carr watches the oil pressure gauge drop to zero. Black…

One pilot in a p-40 named “lulu bell” versus sixty-four enemy aircraft—december 13, 1943, over assam.

At 9:27 a.m. on December 13th, 1943, Second Lieutenant Philip Adair pulled his Curtiss P-40N Warhawk into a climbing turn…

0900, Feb 26, 1945—on the western slope of Hill 382 on Iwo Jima, PFC Douglas Jacobson, 19, watches the bazooka team drop under a Japanese 20 mm gun that has his company pinned. In black volcanic ash, he grabs the launcher built for two men, slings a bag of rockets, and sprints across open ground with nowhere to hide. He gets one rise, one aim—then the whole battle holds its breath.

This is a historical account of the Battle of Iwo Jima (World War II), told in narrative form and intentionally…

At 0700 on October 4th, 1943, Colonel Hubert Zmpy stood on the hard stand at RAF Hailworth and watched mechanics fuel 52 Republic P-47 Thunderbolts for a bomber escort run deep into Germany.

Just after dawn on October 4th, 1943, Colonel Hubert Zemke stood on the hardstand at RAF Halesworth and watched mechanics…

THE DAY A U.S. BATTLESHIP FIRED BEYOND THE HORIZON — February 17, 1944. Truk Lagoon is choking under smoke and heat, and the Pacific looks almost calm from a distance—until you realize how many ships are burning behind that haze.

February 17, 1944. The lagoon at Truk burns under a tropical sky turned black with smoke. On the bridge of…

A B-17 named Mispa went over Budapest—then the sky took the cockpit and left the crew a choice no one trains for

On the morning of July 14, 1944, First Lieutenant Evald Swanson sat in the cockpit of a B-17G Flying Fortress…

End of content

No more pages to load