The sound of the heart monitor echoed steadily in the quiet room, a metronome reminding Margaret Anderson—Maggie to anyone who had ever loved her—that time was still moving even when she couldn’t. She was thirty‑seven and felt ancient. The fluorescent wash turned everything a shade too blue, too clean, the way hospitals try to make you forget life is messy and fragile. Her skin had thinned until the IV tape left little moons, and when she lifted her hand the bones showed like telegraphed secrets. Outside Rush University Medical Center, Chicago snow tumbled in lazy sheets, clinging to traffic lights and the shoulders of night‑shift nurses hurrying through the gusts.

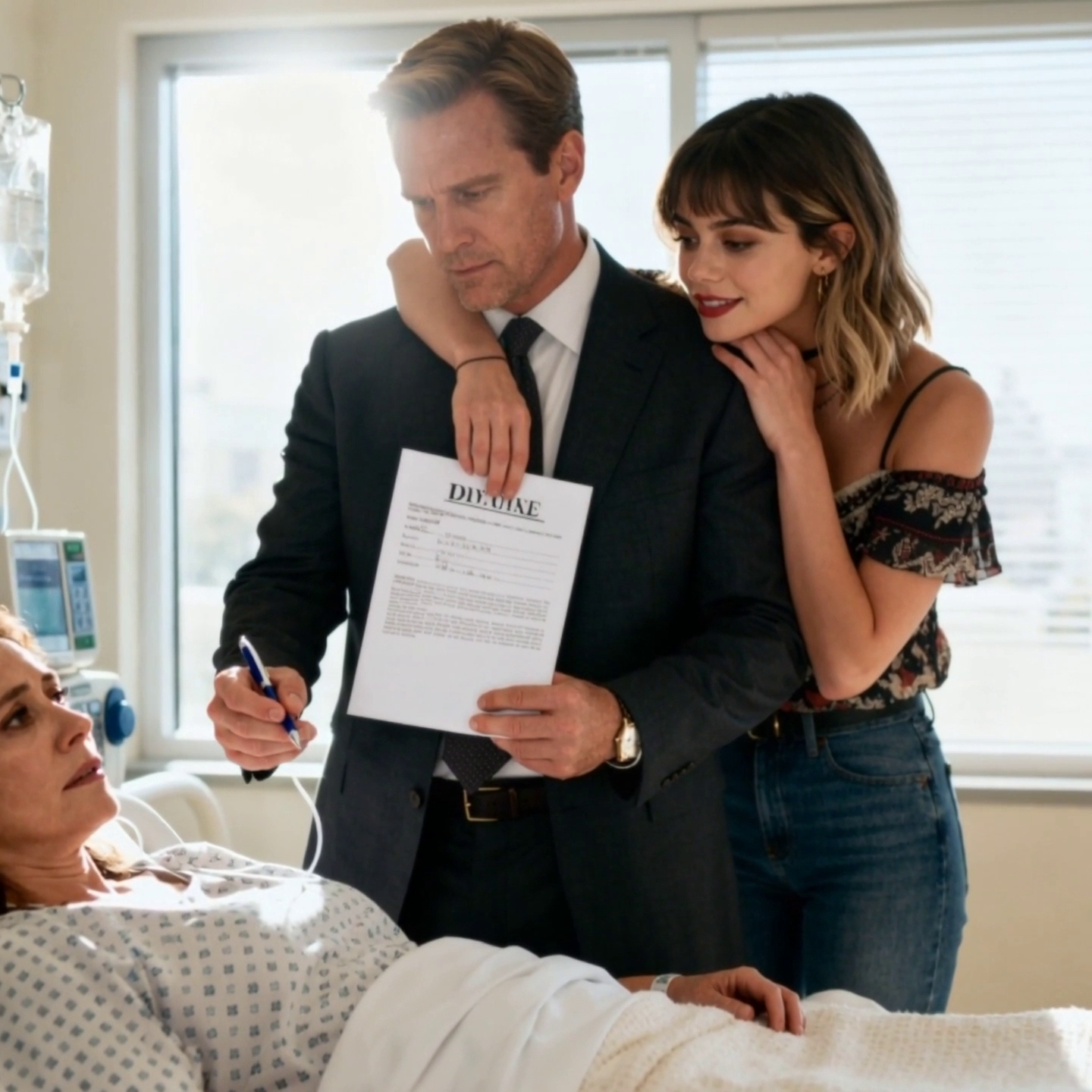

The door opened and Richard came in without a flower or a joke or even that reflexive flash of worry husbands fumble when they don’t know what to say. He wore his winter coat unbuttoned as if he owned the air. He set a leather folder on the rolling tray, the kind he carried to depositions when he wanted opposing counsel to see the grain and think of money. His eyes moved past the IV tree and the pulse oximeter as if they were furniture.

“Maggie,” he said, soft and careful, the voice he used for juries.

She swallowed. “What time is it?”

“Late. I didn’t want to wake you.”

“I wasn’t sleeping,” she said, and her mouth went dry. She watched his hand flatten on the folder. She had married those hands—their steadiness, the promise in them. Tonight they looked like tools.

“We need to talk about the future.”

She tried to smile. “That’s what I’ve been buying with all this poison.” She glanced at the IV bag, the chemo line quietly dripping. “An inch of future at a time.”

He didn’t smile back. He drew out the papers, smoothing each corner. “This will make everything easier. You don’t want your estate tied up. Probate is a swamp. If—if things go the way the doctors think… it’s cleaner to decide now.”

“Estate.” The word fell wrong in her mouth. “Richard, I’m your wife.”

His face hardened by degrees, like ice forming on a lake. “I can’t live like this anymore.” He said it with the flatness of a clause. “I’ve moved on.”

The monitor kept time. Somewhere down the hall a cart squeaked, a door clicked, a nurse murmured something gentle. He nudged a pen toward her.

“Divorce?” she whispered.

He coughed, a lawyer’s stall. “It’s just paperwork. You don’t want me to be financially exposed if… You always said you hate mess.”

She couldn’t reach fury. Her body had spent its rage on fever and on the slow hard labor of continuing. What rose instead was a clarity so cold it felt like grace. If he could do this, he was already gone.

A nurse stepped in, drawn by the rhythm people carry when something is wrong. She was mid‑forties, sharp‑eyed, exhausted. “Everything okay here?”

“My wife would like to sign documents,” Richard said smoothly. “But her hands are weak. Could you… help guide?”

The nurse glanced at Maggie, at the IV, at the chart clipped to the end of the bed where the words STEROIDS and SEDATION pinned like moths. “Is this what you want?” she asked.

Maggie opened her mouth and found only sand. She could not summon the breath to make the sentence that would save her life. The nurse hesitated—one of those crowded seconds that decides the shape of years—and then, believing a husband and a patient had agreed on a thing, she slid a clipboard under Maggie’s palm and supported her fingers. The pen scrawled a half‑name, the letters falling downhill.

Richard exhaled like a man stepping out of weather. He kissed her forehead without touching her and whispered, “Goodbye, Maggie.”

The door sighed shut behind him. The monitor counted on. She stared at the jittering line on the screen and thought: He did not bring a notary. He does not need a witness if he plans to lie about one. He knows every inch of the loopholes I never learned to fear.

Later, when the steroids finally shook out of her and the nurse with the tired eyes came back on rounds, Maggie said hoarsely, “Was there a notary?”

The nurse frowned. “He said one was on the way earlier. I—I stepped out when that woman in the navy blazer came in. Could have been.” She hesitated. “I’m sorry. If you didn’t want—”

“It’s not your fault,” Maggie said, surprised to find she meant it. “Some men are born with the tone of authority. It tricks people into moving things for them.”

She didn’t die. The doctors were careful to make the phrase boring. “Responding to treatment” is how they put it, in patient portal updates that landed like whispered rumors. She clawed inch by inch up the steep gravel slope of recovery, slipping back often enough to learn how to fall. When she could walk the corridor without a wheelchair, when the IV bruises faded to yellow moons, when the mirror startled her less, she checked herself out into winter again with a paper bag of meds and a new allergy to illusions.

Richard did not meet her at the curb. He did not answer calls. The house in Lakeview she had decorated with a patient hand and second‑paycheck wisdom no longer knew her code. The cleaning service she’d hired monthly now answered to a different billing name—Anderson + Lindstrom LLP—the merger he had fantasized about but claimed was out of reach. A broker had sold their lake cottage in Wisconsin in an all‑cash transaction two months earlier. A junior associate wearing cufflinks had served her, at a Starbucks on State Street, with a neatly tabbed packet that claimed she had requested the divorce from her hospital bed. The transfer of marital assets, the packet said, had been voluntary, notarized, and “freely executed.”

What remained for her was a walk‑up studio in a South Side brick where the landlord respected no one and the heat clanked like old memories. She bought a space heater from a man who sold things out of boxes he never opened all the way. She balanced a checkbook down to the breath. She learned the CTA by the cadence of its announcements. When a neighbor asked if she needed help with the groceries, she said, “I’m fine,” then lifted the bag herself because the word fine is armor and ritual.

A clinic social worker told her about a nonprofit that took research volunteers who could read fast and were not afraid of bureaucracy. The sign on the door said ARCHIVE: Advocacy & Research for Coercion in Healthcare, but everyone called it Archive like the noun. It lived in a rehabbed warehouse west of the river where the windows made you believe in light again. The director, Annette Caldwell, was sixty with a runner’s ease and a courtroom jaw. “You from the system?” Annette asked, meaning law, medicine, government.

“I was married to it,” Maggie said.

Annette nodded once. “That counts.” She pushed over a stack—case files, affidavits, policy digests. “Learn our language. We’ll learn yours.”

Maggie learned the language. She read until the pages turned transparent. She traced the lines where consent blurs into coercion, where signatures are harvested like crops. She made friends with the smell of laser‑printed paper. She took notes on the sound people make when they recount a betrayal, the way the vowels hitch. She absorbed the case law the way a body takes calories when it has been starved.

On Tuesdays she did intake calls. “Tell me exactly how the clipboard looked,” she’d say. “Who else was in the room?” People told her about morphine, about fear, about husbands who spoke in plural as if a wife’s body were community property. She rarely told them her story. She did not want to crowd theirs. But sometimes, late, when the office emptied out and the industrial heater hummed, she would picture the nurse’s tired eyes and the pen tilting in her hand, and she would put her forehead on her desk and let the tears come quietly like rain finding the eaves.

The body answered discipline. She ate like a person with a plan. She walked the Lakefront Trail in slushy springs, ran it when summer finally remembered Chicago. She cut her hair short because hair can be a story you no longer owe anyone. She bought two dresses that fit the woman she was becoming: black fabric that did not ask permission to take up space. She memorized the names of prosecutors in the Northern District of Illinois the way other people learn bands.

Richard prospered like mildew. He partnered with Lindstrom, a sleek boutique firm that billed as if time were a substance you could mine. He hired a paralegal named Stephanie whose LinkedIn photo looked like an ad for beginning again. They moved into the Lakeview house and painted over the dining room’s robin’s‑egg blue with a color called Baltic Forged, which the internet told her was “a sophisticated navy for men who collect wines they never drink.” The Tribune ran a piece on his philanthropic work. He posed with a check the size of a door. He cut corners in ways that looked like mastery until you knew what mastery was.

Maggie watched without becoming a watcher. She knew how surveillance curdles men into believing they are still the protagonist. Instead, she built. She built patience into an instrument. She met people who did not like Richard as much as they had pretended to. One was a junior partner who had spent too many Thursdays explaining missing funds to clients with calm voices and clenched jaws. Another was a forensic accountant named Leah Torres who wore her hair in a coil and her skepticism like a badge. “Show me the books he wants no one to see,” Leah said the first time they sat down at a coffee shop where the milk froth pretended to be snow.

“What makes you think there are books?” Maggie asked.

Leah smiled without warmth. “Men like Richard keep doubles. You don’t steal from clients in the open. You do it with shell games and trust accounts and wire transfers at 3:17 p.m. on Fridays.”

Maggie went back to the hospital. She brought flowers for the nurse with the tired eyes, whose name she learned was Rowena Pike. “I need to ask you something that may ache,” Maggie said.

Rowena took off her gloves and sat on the edge of a chair. “I’ve been waiting for you to come back,” she said simply.

“Was there a notary?”

Rowena’s face changed. “There was a woman in a navy blazer. She had a seal. The problem was—” She paused, looking for the precise place the truth begins. “You were on IV hydromorphone. Your hands were trembling. You asked what you were signing. He said, ‘It’s what we discussed.’ You nodded, but—” She blew out a breath. “I’ve testified before. If someone asked me, I’d say your decision‑making was impaired. And I would say I shouldn’t have helped—no matter what he said.”

“You were trying to help me be who you thought I wanted to be,” Maggie said, meaning it without bitterness.

Rowena nodded once. “We listen for consent. We’re not trained to un‑hear power.” She took out her phone. “We’ve got security footage timestamps. I can’t give you the footage without a subpoena, but I can swear to the times. And the chart shows your meds. Records like to be looked at.”

“Would you swear?” Maggie asked.

Rowena’s jaw set. “Under oath.”

The plan did not arrive whole. It accreted. A timestamp here. A name there. A corporation registered in Delaware on a Wednesday and abandoned on a Friday. A cashier’s check. A donation that did not match the firm’s income stream. Leah traced wires like a cartographer, drawing maps of where the money vanished and where it would have gone if it had hands. Andrew Kincaid, a business journalist who had been demoted after irritating a donor, bought Maggie lunch at a diner that smelled like pancakes and ink and said, “If I can corroborate two things, I can run the third.”

“What two?” she asked.

“The IOLTA transfers,” he said. “And the offshore account.”

“Offshore?”

“You don’t need a beach,” Andrew said, tapping his notebook. “You just need a bank that likes secrets.”

She did not live for revenge. She lived for morning coffee that tasted like a decision, for the Lake Michigan wind on days when it remembered mercy, for the way her body felt after four miles of running on a path she did not owe anyone. But revenge worked like gravity in the background, tugging everything toward a point. On the third anniversary of the night her name slid downhill across paper, she circled that date in her head and felt how the city itself seemed to lean toward it.

The week before, a whisper began in the legal press. An anonymous packet hit a reporter’s desk at the Tribune: internal emails about client trust accounts at Anderson + Lindstrom that didn’t reconcile, transfers to an entity called Prairie North Advisors LLC, a firm no one could find a real office for. Another envelope found its way to the Attorney Registration and Disciplinary Commission, bulging with copies of ledger pages seemingly written by two different hands—but mostly by a man who thought no one could tell he had been hurrying.

Richard called it a misunderstanding. He called his bookkeeper sloppy. He called his clients impatient, his detractors jealous, his accusers vague. He said these things at a charity gala in a house with her old floorboards under other people’s shoes. He stood in the foyer where they had once put a Christmas tree because the ceiling was high enough to make small desires look noble.

Maggie did not wear armor. She wore the black dress that fit like language she knew by heart. She walked up the front steps with an invitation borrowed from a man who had decided three bourbons earlier that he admired courage. The night smelled like good cologne and expense. The sky over the lake was a lid, low and heavy. Inside, a string quartet threaded the noise with polite music.

When Stephanie saw her, she made a sound like a glass being set down too hard. “Maggie?”

“Hello, Stephanie,” Maggie said, and her voice surprised her with its calm. “You look well.”

Richard turned as if someone had said his name in a language he had once spoken fluently. He paled, then colored, then arranged his features into courtroom neutral. “You’re trespassing.”

“No,” Maggie said, and took a folded paper from her clutch. “I’m returning.” She lifted the folding so only he could see the header: Cook County Circuit Court, Chancery Division. “And this time I brought a notary.” She slipped the paper away again. “Relax. You’ll get yours in the morning.”

He smiled a thin, courtroom smile. “Security.”

“Call them,” she said. “But before you do, you’ll want to see the slideshow.” She nodded toward the far wall where, across a bank of windows, a projector cast the gala’s sponsor reel—logos and names and gratitude—followed by a slide labeled THE IMPACT OF GIVING. The next slide was supposed to be about scholarships. It wasn’t.

Images filled the wall. Ledger lines. Wire confirmations. A receipt from a bank in George Town, Grand Cayman. A screen capture of a late‑night transfer from a client trust account ending in 7334 to Prairie North Advisors LLC, routing through a correspondent bank nobody used for above‑board things. The room made a soft collective sound, the hush of people recognizing they are present at a moment that will be repeated without them.

“Turn that off,” Richard said, suddenly raw. He moved toward the projector. He stopped halfway as two men in suits intercepted him—board members who had learned to smell risk like smoke. “What is this?” he demanded, but his voice had lost its jury timber.

“It’s what you built,” Maggie said. “And how you built it.” She kept her voice low, for him, for the woman she had been. “You took my home when I was too medicated to fight you. You took clients’ money when they trusted you to hold it. You took your paralegal to dinner the week after I signed. If there is a difference between those things, it is only what state code governs the consequence.”

Faces turned. Phones came out like moths. A donor whispered to another donor who whispered to a reporter who was not supposed to be invited. The string quartet stopped abruptly on a chord that sounded like breath held.

“None of this is admissible,” Richard said, and even he heard how weak that sounded in a living room.

“It will be,” Maggie said. “Because this is only what people get to see when they’re wearing tuxedos. The rest is already somewhere quieter.” She tapped her clutch. “Cook County State’s Attorney has the affidavit from Nurse Rowena Pike, who watched you put a pen in my hand while I was under hospital sedation. We have the pharmacy records for the hour you hurried me along. The Attorney Registration and Disciplinary Commission has your trust account ledgers from the months you called busy. The feds have your wires.”

“You never could resist a speech,” he said, but the edge was gone; he sounded like a man negotiating with a storm.

“I learned them from you,” she said, and for a moment the two of them occupied the same memory: a wedding toast in a sunlit room, words about partnership and faith and plans. The memory flickered and passed.

Security arrived with the hesitation of people who suspect they are about to become witnesses. They didn’t lay hands on anyone. They did not need to. By then, the gala had shifted from celebration to observation. People parted to let Maggie pass as if she had been given some ceremonial role she had not asked for.

She walked the house like a museum, remembering the small mercies of good light in the kitchen at four p.m. and the thrill of a first mortgage payment. In the bedroom she and Richard had painted together one fall weekend when it seemed like time would only ever be plentiful, she paused to look out at the lake, dark and blank as a verdict. Then she went downstairs and walked past the projector, which had gone mercifully black, and out into the night.

The Tribune piece ran two days later, careful and cold. It quoted sources who would later deny they had spoken and people who would later remember they had warned. The ARDC opened an investigation with a stern sentence that left room for men like Richard to imagine it was a misunderstanding until it wasn’t. Leah’s maps became exhibits. Andrew’s notes became paragraphs. Archive’s office filled with the sound of printers making more paper to carry the weight of proof.

Richard called. He left three messages, then five. “This is unnecessary,” he said on one. “We can negotiate,” he said on another. “You don’t know what you’re doing,” he said on a third, and she hit delete before the end because she knew exactly what she was doing and there was fury in knowing he still thought she didn’t.

When the indictment came, it arrived as plain text, without adjectives. United States of America v. Richard M. Anderson. Counts: wire fraud, bank fraud, mail fraud, money laundering. The words launder and fraud do not sit well together; one is soap and the other is grease. You don’t have to be a poet to see how those words argue in a man’s name.

Stephanie left gently, like someone backing away from a sleeping animal. She moved into a one‑bedroom near DePaul and learned how to make eggs. She called Maggie once, her voice steady. “I am sorry,” she said. “He told me you had asked him for a divorce in the hospital. He said you wanted him to have everything because you didn’t want to be a burden.”

“He’s good at sentences,” Maggie said. “Take care of yourself.”

“I meant the house,” Stephanie said, surprising her. “He told me he had always wanted it. He said it was his even before you two bought it, because he had dreamed it first. That’s the kind of man he is.”

“I know,” Maggie said, and after she hung up she went for a run because sometimes the only thing you can do with a fact is move your body through it until it loosens its grip.

Civil court was slower. It is supposed to be. Equity asks to be courted. Maggie filed to set aside the transfers for undue influence and lack of capacity. The phrase constructive trust became a prayer. Rowena’s affidavit walked into the courtroom on paper and then in person, where she said calmly into a microphone that Maggie had been too medicated to understand, that Richard had spoken over her, that a woman in a navy blazer with a notary’s seal had appeared and left quickly, that it had haunted her, that she had been waiting for this day, that the truth felt like a weight leaving her hands.

The judge had a face like a boulder and an ear for the music of attorneys when they lie. He looked at Richard’s counsel the way a man looks at a rotten fence post. He asked questions about timing. He asked about the notary, whose name did not survive scrutiny. He asked why a husband moved this fast. He used the word unconscionable the way you use a knife to test a melon. When he granted a preliminary injunction freezing certain assets and restoring Maggie’s claim to the Lakeview house pending final judgment, Maggie kept her face still because she had learned that triumph is a poor actor. But later, she sat on a bench outside the courthouse with Annette and Leah, and she let herself breathe like a woman who had swum to a dock and could, finally, uncramp her hands.

The criminal case spun on. Richard wore the kind of suit men put on when they want a jury to believe in order. He sat very straight, as if posture could exculpate. The government’s exhibits were beige and boring and lethal. Wire confirmations in stacks so tall the cart wheels squeaked. Bank officers with brittle smiles. Clients who did not cry because they had cried already. The jury looked the way juries look when they understand that a man found it easier to take than to ask.

One morning in late fall when the ginkgoes threw their coins across the sidewalks, Maggie came down the courthouse steps as Richard came up. Reporters clotted the stairs. He saw her. Something passed through his face that she had never seen before—a recognition that the axis had shifted and would not move back. He opened his mouth. He closed it.

“You destroyed our marriage,” she said quietly, not for the microphones but because it is good to put the right words into the air where the wrong ones have lived too long. “You didn’t destroy me.” She stepped past him. The cameras swung. He stood for a second as if he had forgotten how to go forward.

In the judgment that eventually bore her name and his, the court wrote sentences so careful they could balance a house. The transfer of assets was set aside for undue influence and lack of capacity. The Lakeview property, upon final accounting and the satisfaction of outstanding liens and equities, returned to her with the worn floorboards she had sanded once on a summer afternoon. She did not move back in immediately. Houses can hold weather for years.

She kept working at Archive. People sent letters from rooms that smelled like disinfectant and grief. They asked: “Do I have to sign?” They asked: “What will happen if I say no?” She answered the way she wished someone had answered the night the nurse asked if this was what she wanted. “You don’t sign when you’re scared and medicated,” she said. “You don’t sign alone. You don’t sign for someone else’s convenience. If anyone calls it ‘just paperwork,’ you call a lawyer who loves you more than your husband loves control.”

Annette asked her to start something formal. “A project with a name people can say when they’re in rooms like the one you were in.”

Maggie called it Quiet Sign. She thought of calling it Loud No, but people in hospital rooms don’t always have volume. Quiet Sign built kits for families: a laminated card to hang at the bedside that read NO LEGAL DOCUMENTS WITHOUT MY ATTORNEY PRESENT; a list of hospital ombudsmen; a script for nurses to use when a relative asked for something they should not have. They trained notaries on capacity and coercion. They made it harder to steal with tone.

On a spring afternoon three years and some days from the night Richard slid paper across the tray table, Maggie stood in the Lakeview house with a contractor who talked about joists. The windows were open. The lake looked like an old promise that had finally learned to make itself small and true. She ran her palm along the wall where a dent still lived from the time a Christmas tree had tried to topple. She bought a rug that did not apologize for being beautiful.

The doorbell rang. She thought of packages and signatures and small errands. When she opened the door, Stephanie stood on the stoop with a paper bag, cheeks pink from the wind. “I came to say congratulations,” she said. “And to return this. It’s yours. Not the contents—those are mine now—but the idea of it.” She held up the bag. “It’s just a casserole dish. But I want to live in a world where things find their way back.”

“Come in,” Maggie said. She meant it. She made tea because some conversations go better when you hold something warm. They talked about law and luck and the way certain men could rearrange a room without touching anything. They talked about the thin relief of waking up and discovering you are free.

When Stephanie left, Maggie sat on the floor in the square of afternoon sun and let the heat find her bones. She thought of Rowena, who had sworn under oath and slept better since. She thought of Leah drawing maps that turned into exhibits. She thought of Annette finding language where other people found only pain. She thought of how the heart monitor had counted down a night when she believed there would be no more nights, and how sometimes the body keeps its quiet promises.

People asked her, later, if revenge had tasted sweet. She never said yes or no. She said it tasted like clean water after a long run. It tasted like a plan that ends by handing somebody else a tool you no longer need. It tasted like the word enough spoken calmly in a room that used to make you shake.

On a morning when the sky over the lake started pale and then remembered how to be brave, she laced her shoes and ran. She passed couples with coffee and a boy on a scooter and a woman on a bench talking to someone who was making her laugh in the way you laugh when you have remembered laughter is a choice. She ran until the path turned under her, familiar as a prayer you can finally say without pleading. The wind lifted off the water and hit her square. She leaned into it, and for a long, good minute, she did not think of anything at all.

In court, months later, a judge accepted a plea. Men like Richard rarely gamble on juries when paper is this patient. He stood, and the room smelled like anxiety and floor cleaner, and he said the word guilty as if it were a foreign coin he had just found in his pocket. He talked about remorse. He talked about pressure. He did not talk about the night in the hospital, the way power taught his mouth how to shape requests like commands. He did not say the word love because even he knew better than to defraud that.

When he was sentenced, the number was not poetic. Years rarely are. He looked for her in the gallery and found an empty place where he had expected a face. She was at Archive that day, writing a grant proposal to put Quiet Sign cards in smaller hospitals, the ones that remember people by name and debt. She ate a sandwich at her desk and underlined a sentence about training notaries in rural counties, and she did not feel triumph. She felt that a circle had closed around a simple rule: you do not take from the sick.

That evening she walked home along a street where the trees arched into each other and made a green tunnel. She thought of the version of herself who had watched a pen wobble toward her name. She wanted to tell that woman she would live, and more than live. She wanted to tell her about the Lakefront wind and the way sunlight returns to rooms that have housed sorrow and the fact that one day she would stand barefoot on her own floor and not brace for loss.

She let herself into the house and set her keys in a bowl and opened the windows. The lake breathed; the curtains lifted. In the kitchen she took down a casserole dish that had been to other lives and back again. She set it in the sink and filled it with warm water and a little soap and watched the suds raft against the rim. Then she went to the desk by the window and wrote a note to a woman in Joliet who had called that morning, scared. It began: You do not sign tonight. And if anyone tells you it’s just paperwork, you tell them you have people now.

Maggie folded the note and sealed the envelope and pressed it flat with the heel of her hand. Her body was her own. Her name was hers. Outside, the lake kept its slow, steady sequence against shore, a heartbeat you could set your life by.

News

As I lifted her veil to say “I do,” my 13-year-old son shouted, “Dad, look at her shoulder!”—a butterfly-shaped birthmark came into view—and her confession about what happened at eighteen left the entire chapel stunned.

I was about to say “I do” in a cedar‑framed chapel off Hendersonville Road, the kind with hand‑stitched kneelers and…

An 8-year-old girl clung to an old wardrobe for 30 days — her mom thought it was just a game, until a rainy night when she opened the door and was left speechless.

She was eight, and she guarded the old wardrobe as if her small body could hold back the whole world….

“Mom, that’s my brother!” — The 4-year-old points at a child huddled on the steps; the millionaire mother turns, sees the two of them together, and falls to her knees, weeping — a years-old secret exposed in the middle of the street, and a home opens its doors at once.

Claire Atwood never planned to cry on Maple Street. She planned to make the eight-thirty board prep, charm the nine…

“You’re not welcome here—haven’t you freeloaded enough?” — Thrown out of my own son’s wedding by the bride, I didn’t argue; I simply walked out, took out my phone, and dialed one number. What happened at the wedding the next day left them pale.

I never imagined the day my only son would marry would end with his fiancée ordering me out of a…

A stranger gave up the last-minute seat on Christmas Eve so I could get home and surprise them—but through the window, my husband and my “best friend” were clinking glasses; on the porch, my daughter was curled up and crying—I didn’t knock, I set a silent plan in motion.

The gate smelled like coffee, damp wool, and hurry—the particular brand of hurry that clings to airports on Christmas Eve…

“The table is full!” — My mother’s Christmas-Eve words pushed my 16-year-old daughter out the door while I was on an ER shift; I didn’t cry or argue — I got tactical. And the letter on the doorstep the next morning made the whole family go pale…

I was still hearing the alarms when I turned the key and pushed into the quiet. That sound—the flatline, the…

End of content

No more pages to load