Just after dawn on October 4th, 1943, Colonel Hubert Zemke stood on the hardstand at RAF Halesworth and watched mechanics fuel fifty-two Republic P-47 Thunderbolts for a bomber-escort mission deep into Germany. He was twenty-nine, with six months of combat behind him and four confirmed kills. The Luftwaffe had massed one hundred and eighty fighters—Focke-Wulf 190s and Messerschmitt 109s—to defend the industrial targets the bombers would strike that morning.

Every pilot climbing into those cockpits knew the numbers.

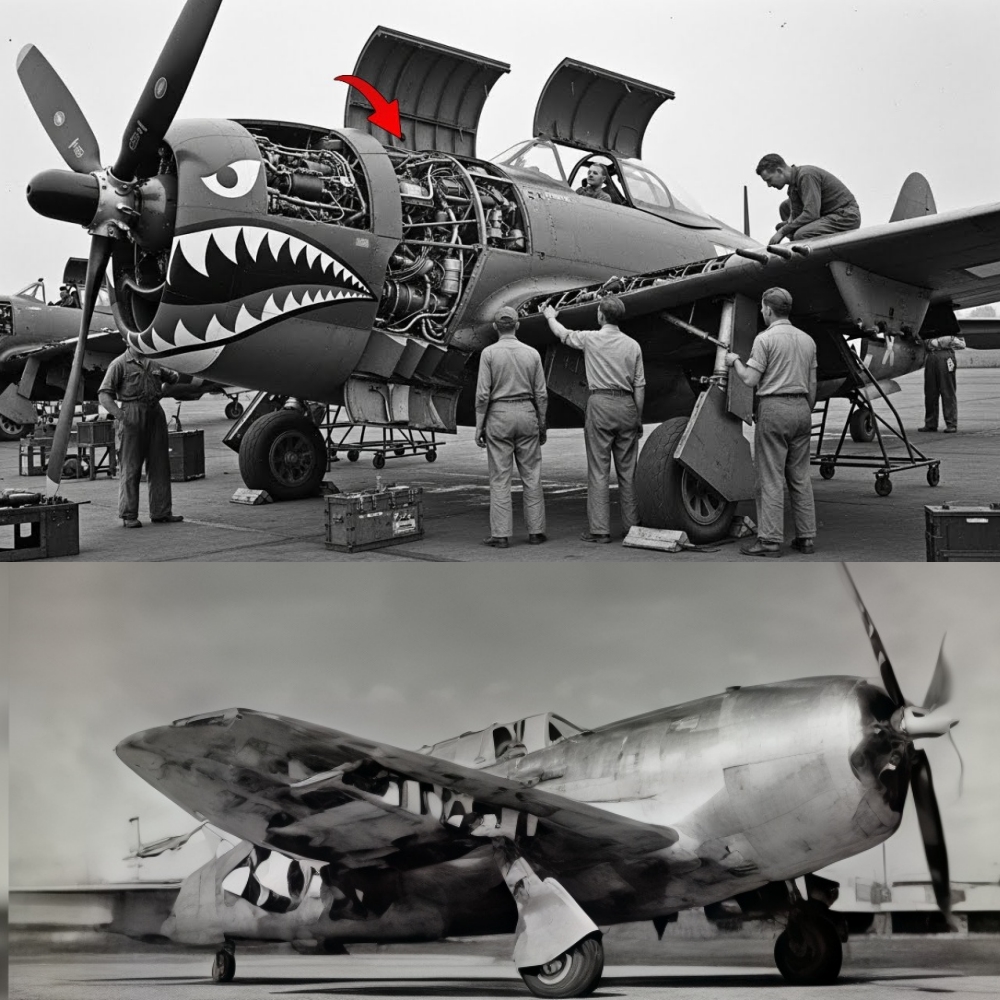

A P-47 Thunderbolt weighed seven tons empty. A German Focke-Wulf 190 weighed less than four. In a turning fight, physics won. The lighter fighter turned tighter. The heavier fighter died.

Zemke’s 56th Fighter Group had lost eleven aircraft in their first four months of combat. Four pilots were killed. Seven were captured. The Germans called the Thunderbolt the Jug—short for juggernaut—a flying tank that couldn’t dogfight.

American bomber crews watched P-47s try to protect them and saw the truth. When Focke-Wulfs attacked, the Thunderbolts couldn’t stay with them through the turns. Luftwaffe pilots broke away from bomber formations, knowing the heavy American fighters wouldn’t follow through vertical maneuvers.

They were right.

On June 26th, 1943, Zemke’s group engaged Jagdgeschwader 26 over France. Veteran German pilots flew circles around the P-47s—literally. Five Thunderbolts went down. Four American pilots died. Captain Robert Johnson barely made it home with his aircraft shot to pieces. His Thunderbolt had taken more than two hundred cannon hits and still flew.

But it hadn’t won the fight.

The mathematics were simple. A Focke-Wulf 190 could turn inside a P-47 every single time. At fifteen thousand feet, the German fighter completed a 360-degree turn in twenty-two seconds. The Thunderbolt needed twenty-eight.

Six seconds.

In combat, six seconds could decide everything.

Eighth Air Force generals watched their fighter group struggle and made plans to replace the P-47 with the new P-51 Mustang—lighter, faster, better in level flight, with better range. The Thunderbolt program looked like a failed experiment. Five other fighter groups were scheduled to transition to Mustangs by the end of 1943.

But Zemke had spent two years testing the P-47 before the war. He knew something the Germans didn’t.

The Thunderbolt couldn’t turn.

It could dive.

The massive Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp produced two thousand horsepower. The thick wing and heavy airframe stayed stable at speeds that would tear a Focke-Wulf apart. In a vertical dive, nothing in the Luftwaffe could catch a Thunderbolt.

So Zemke stopped trying to fight the war the Germans expected.

He built new tactics around what the P-47 actually was: height advantage, diving attacks, hit-and-run passes. Never turn with the enemy. Dive through the formation. Use speed and momentum. Zoom back to altitude. Attack again.

The 56th practiced through the summer of 1943—dive-bombing runs on ground targets, high-speed gunnery passes, energy management. Every pilot learned to think in three dimensions. Use altitude like currency. Trade height for speed, speed for position. Never get slow. Never try to turn.

By September, Zemke’s pilots were ready, but Eighth Air Force bomber losses were accelerating. On September 17th, missions to French targets cost eight B-17s. German fighters hit the formations before American escorts arrived. The bombing campaign was failing.

October 4th would be different.

Zemke planned to put his new tactics into a full combat test: fifty-two P-47s, all diving from altitude, all using speed instead of turning, all trusting the mathematics he had worked out.

If you want to see how Zemke’s diving tactics worked against the Luftwaffe, consider sharing this story. It helps more readers find pieces like this. If you follow our work, you’ll see more stories from the archives.

Back to Zemke.

The mission brief that morning included one detail that changed everything. The bomber stream would fly at twenty-two thousand feet. Zemke positioned his Thunderbolts at thirty thousand—eight thousand feet above the bombers, eight thousand feet of potential energy ready to convert into diving speed. By noon, the 56th Fighter Group would either prove the P-47 could win or watch their bombers fall.

German radar stations tracked the American formation crossing the Dutch coast mid-morning. Luftwaffe controllers scrambled Jagdgeschwader 1 and Jagdgeschwader 26 to intercept. Seventy-three Focke-Wulf 190s climbed toward the bomber stream.

German pilots expected what they always saw: American fighters flying tight formation alongside the B-17s, easy targets forced to maneuver slowly to stay with the bombers.

But Zemke’s 56th wasn’t escorting the bombers.

They were hunting—eight thousand feet above.

Not long after the coast, Zemke spotted the German formation assembling fifteen miles ahead of the bombers at eighteen thousand feet. The Focke-Wulfs were climbing into attack position, following standard Luftwaffe doctrine: gain altitude advantage, dive through the bomber formation, use speed to escape before the escorts could react.

Zemke rolled his P-47 into a seventy-degree dive.

Fifty-one Thunderbolts followed.

Seven tons of aircraft and ammunition accelerated toward terminal velocity. The massive propeller bit into thin air. The Double Wasp roared at full military power. Airspeed needles climbed past three hundred miles per hour, past three-fifty, past four hundred.

The German fighters never looked up. Their eyes were fixed on the bombers below.

They didn’t see fifty-two P-47s screaming down at four-fifty until Zemke’s first burst of .50-caliber fire ripped through a Focke-Wulf’s cockpit. The German pilot never pulled out of his climb.

What happened next lasted ninety seconds.

Fifty-one more Thunderbolts punched through the German formation at speeds the Focke-Wulfs couldn’t match. Each P-47 carried eight Browning M2 machine guns. Each gun spat eight hundred rounds per minute. The combined firepower of the group put sixty-eight thousand rounds into the sky every sixty seconds.

German pilots tried to break. They tried to turn. They tried to dive away.

But the physics were wrong.

A Focke-Wulf at four hundred miles per hour couldn’t pull out of a dive as quickly as the heavier P-47. The Thunderbolt’s thick wing and massive structure handled the G-forces better. German pilots blacked out trying to match the American pull, or their aircraft came apart under the stress.

Zemke’s wingman, Lieutenant Walter Cook, watched a Focke-Wulf try to dive away. The German pilot pushed forward and went vertical. Cook stayed with him. At five hundred miles per hour, the Focke-Wulf’s right wing folded backward and tore off. The wreckage tumbled toward Dutch farmland.

The remaining Thunderbolts didn’t dogfight. They didn’t try to turn with the Germans.

Each pilot made one high-speed pass—fire, dive through, then use the remaining speed to climb back to altitude for another strike.

Zemke had calculated this exactly. The Thunderbolt’s engine produced enough power to regain eight thousand feet in four minutes.

Four minutes.

Then they could dive again.

The German formation scattered. Pilots who moments earlier were preparing to attack B-17s were suddenly fighting for their own survival. They couldn’t climb fast enough to escape the diving Thunderbolts. They couldn’t dive fast enough to outrun them. They couldn’t turn, because the P-47s never committed to turning fights.

Eleven minutes after the first attack, the sky above the bomber stream was empty of German fighters. The Focke-Wulfs that survived fled east toward their airfields.

Not one German fighter made it through to attack the B-17s.

Zero bombers lost.

Zemke’s group reformed at altitude and continued the escort. The bombers hit their targets without interference. On the return leg, more Luftwaffe formations appeared in the distance. None came close enough to engage.

The 56th landed back at Halesworth in the early afternoon. Ground crews counted ammunition expenditure. Gun cameras were pulled for film development. Intelligence officers began debriefing.

The initial reports sounded impossible. The group claimed twenty-one confirmed German fighters destroyed, another eight probably destroyed, sixteen damaged—zero American aircraft lost, zero pilots wounded.

Eighth Air Force headquarters demanded verification.

Investigators interviewed every pilot separately. They analyzed every inch of gun-camera footage. They cross-referenced radar tracks and radio intercepts. Every claim checked out.

October 4th, 1943 was real.

But it was one mission—one day.

The Luftwaffe still had hundreds of fighters. The strategic bombing campaign would continue for eighteen more months.

Could Zemke’s tactics work consistently?

Could other fighter groups learn them?

Could the P-47 actually win the air war over Europe?

Three weeks later, the 56th Fighter Group would answer those questions in a way that terrified the Luftwaffe.

October 1943 became the 56th’s proving ground. Eighth Air Force scheduled maximum-effort bomber missions every day the weather allowed: Bremen, Münster, Wilhelmshaven, Düren—industrial targets deep in Germany. Each mission drew a massive Luftwaffe response.

Escort to Bremen. The group intercepted forty Messerschmitt 109s forming up to attack the bomber stream. Same tactics: high position, diving attacks. Six German fighters destroyed. Zero American losses.

Then the monster raid. Sixty Focke-Wulfs tried to break through. Zemke’s pilots hit them in three successive diving passes. Nine confirmed kills. Two probables. The bombers completed their mission without losing a single aircraft to fighter attack.

Then October 14th.

Eighth Air Force launched the second Schweinfurt raid. Two hundred and ninety-one B-17s targeted ball-bearing factories critical to German war production. The Luftwaffe threw everything available into defending Schweinfurt—over three hundred fighters.

This was the decisive battle both sides knew was coming.

Zemke wasn’t flying that day. He was at Eighth Air Force headquarters receiving the British Distinguished Flying Cross. His deputy commander, Lieutenant Colonel David Schilling, led the 56th into combat.

Schilling followed Zemke’s system exactly: position high, wait for the German formations to commit, dive through at maximum speed.

But the scale of the battle overwhelmed every escort group. Too many German fighters, not enough American escorts.

The math didn’t work.

Sixty-eight B-17s went down. Six hundred and eighty American airmen were killed or captured in one afternoon. Schweinfurt became the worst single-day loss of the war for Eighth Air Force.

The 56th claimed sixteen German fighters destroyed that day—more than any other escort group.

But it wasn’t enough.

The bombers kept going down. The daylight offensive looked finished. Losses were unsustainable. German fighter production was accelerating.

After Schweinfurt, Eighth Air Force commanders debated suspending deep-penetration raids until long-range P-51s arrived in sufficient numbers. Some generals argued the P-47 had proven inadequate regardless of tactics—too short-ranged, too heavy, too limited.

Then the weather cleared over northern Germany.

Eighth Air Force launched another maximum-effort mission: the Düren railway yards.

The 56th took off from Halesworth that morning with Zemke back in command. He positioned his group at thirty-two thousand feet—ten thousand above the bomber stream.

German fighters rose to meet the B-17s. Zemke counted seventy-three contacts: Jagdgeschwader 26 and elements of Jagdgeschwader 3, some of the Luftwaffe’s most experienced pilots. The German formation leader was Major Wilhelm Ferdinand Galland, younger brother of Luftwaffe General Adolf Galland.

Fifty-five confirmed victories. Seven years of combat.

He’d fought in Spain, Poland, France, and Russia. He knew every fighter tactic the Luftwaffe taught.

Galland positioned his gruppe for a classic bounce on the bombers. His fighters held altitude advantage. His pilots were in perfect formation.

They began their dive.

Zemke was already diving.

His fifty-two Thunderbolts had two thousand feet more altitude than the German formation. They hit from above and behind at four-seventy.

The Germans never saw them coming.

The combat lasted seven minutes.

Seventeen German fighters went down in that window. Galland’s Focke-Wulf took multiple .50-caliber hits in the engine and cockpit and went into an uncontrolled spin from twenty-three thousand feet.

Major Wilhelm Ferdinand Galland did not survive.

The Luftwaffe lost one of its most experienced leaders in a battle that lasted less time than it takes to boil water.

By the end of October, the 56th had flown nine major missions in one month. Their confirmed kill total for October was thirty-nine German aircraft destroyed. The group that “couldn’t dogfight” had become the highest-scoring unit in Eighth Air Force.

The Germans noticed.

Luftwaffe intelligence began tracking American tactics and identified a new threat. They called it the American diving tactic.

And they had no counter.

In November 1943, Jagdgeschwader commanders held emergency conferences across occupied Europe. German pilots reported P-47s attacking from impossible altitudes at speeds their aircraft couldn’t match.

Traditional intercept doctrine had dominated European skies for four years: gain altitude, position above the enemy, dive through with speed advantage. It had crushed Polish, French, British, and Soviet aircraft by the thousands.

Now the Americans were using it better.

Major G.A.R. commanded Jagdgeschwader 11—two hundred and seventy-five confirmed victories, one of Germany’s most successful fighter pilots. He studied the 56th Fighter Group’s pattern and named the problem.

The P-47 pilots weren’t escorting bombers.

They were hunting fighters.

They ignored the B-17s and went after Luftwaffe formations before they could strike.

Controllers tried to adapt. They sent formations at different altitudes—some high, some low, some from the flanks—to force the American escorts to split and create openings.

It didn’t work.

Zemke layered his squadrons vertically: one at thirty thousand, one at twenty-eight, one at twenty-six. If the Germans came high, the top squadron dove. If the Germans came low, the bottom squadron dove. The middle squadron covered both.

Every P-47 maintained enough altitude advantage to accelerate into attack speed.

Mission to Münster. Jagdgeschwader 1 attempted a coordinated strike with thirty Focke-Wulfs approaching from multiple directions at once.

Zemke’s group intercepted all three formations before they reached firing range.

Fourteen German fighters destroyed.

The bombers lost zero aircraft to fighter attack.

Flak got two B-17s. Fighters got none.

The Luftwaffe began avoiding areas where the 56th operated. Controllers listened to radio traffic and learned Zemke’s call signs. When they heard his group in the sector, they redirected their fighters elsewhere.

Better to miss an attack opportunity than lose experienced pilots.

By late November, Eighth Air Force headquarters recognized what was happening. Other P-47 groups weren’t matching the 56th’s results: the 4th, the 78th, the 352nd—good units with competent pilots, none posting Zemke’s kill ratios.

Eighth Air Force commander General Ira C. Eaker ordered Zemke to brief all P-47 groups on his tactics.

December 8th, 1943. Kings Cliffe airfield.

Every group commander in Eighth Air Force attended. Zemke spent four hours explaining the mathematics.

The P-47 couldn’t turn. Accept that.

Don’t dogfight.

Use altitude. Convert height to speed. Hit fast. Disengage fast. Climb back up. Repeat.

Never get slow. Never turn with the enemy.

Think vertically, not horizontally.

Some commanders resisted. They’d trained in traditional turning combat and close-in maneuvering. Zemke was telling them everything they knew was wrong—for the Thunderbolt.

If the aircraft couldn’t do what doctrine demanded, then doctrine had to change.

Colonel Don Blakeslee commanded the 4th Fighter Group. His unit was scheduled to transition to P-51s in early 1944. He asked Zemke if the diving tactics would work for Mustangs too.

Zemke said, “Yes. Every fighter benefits from altitude and high-speed attacks. But the P-47 needs it. The Mustang has options. The Thunderbolt doesn’t.”

Late in December, the 56th escorted bombers to Osnabrück under heavy overcast and poor visibility. German fighters attacked from inside cloud layers, ambushes that erased the Americans’ altitude advantage.

Eight P-47s took damage. One pilot was killed. Two were captured.

The mission showed the limitation: when weather forced low-altitude operations, the Thunderbolt’s edge vanished.

But clear weather dominated northern Europe through January and February 1944. Perfect conditions for high-altitude work.

The bombing campaign accelerated.

Big Week was coming: six consecutive days of maximum-effort raids against German aircraft factories. Every available bomber. Every available escort. The largest air battle in history.

The 56th would fly all six days.

Their assignment included a target no American fighter had ever reached—Berlin, the German capital—five hundred miles into enemy territory, beyond the combat radius of every escort fighter in the inventory.

Except someone had figured out how to extend the P-47’s range by eighteen percent.

And that someone was about to prove the Thunderbolt could protect bombers all the way to Hitler’s doorstep.

In February 1944, Republic engineers delivered modified external fuel tanks to RAF Halesworth. Each tank held one hundred and fifty gallons. Standard P-47 internal fuel capacity was three hundred and five gallons. With external tanks, total fuel rose to six hundred and five.

Combat radius jumped from two hundred and thirty miles to four hundred and twenty-five.

Berlin was within reach.

The problem was weight.

A fully fueled P-47 with external tanks weighed nine tons at takeoff. The aircraft needed every foot of Halesworth’s runway to get airborne. Once airborne, that fuel weight punished climb performance. German fighters could intercept during the vulnerable climb phase—when American fighters were heavy and slow.

Zemke worked out the solution.

Take off full. Climb slowly to altitude over England. Burn the external fuel first. Drop the empty tanks before crossing into enemy territory.

By the time German fighters appeared, the P-47s would be at combat weight with full internal fuel remaining.

The mathematics worked, but the timing had to be perfect. Drop too early and the fighters wouldn’t reach the target. Drop too late and they’d be too heavy to fight.

Zemke set the drop point over Holland, two hundred miles from base. The fighters would cross the Dutch coast at combat weight with enough internal fuel for two hours of operations.

Big Week began.

Eighth Air Force launched nine hundred and forty-one bombers against German aircraft plants. The 56th lifted off with fifty-four P-47s, each carrying full fuel and full ammunition. Target: Leipzig, four hundred miles into Germany.

The group climbed to thirty thousand feet over the North Sea. External tanks fed the engines during the climb.

Over Holland, all fifty-four pilots toggled their releases at once. One hundred and eight empty tanks tumbled toward Dutch farmland.

Now the P-47s were at combat weight.

Altitude: thirty thousand.

Speed: two-eighty.

Internal fuel: enough for four hours.

German radar tracked the formation. Luftwaffe controllers scrambled every available fighter—Jagdgeschwader 3, Jagdgeschwader 11, Jagdgeschwader 26.

One hundred and ninety German fighters rose to intercept the bomber stream.

The 56th moved ahead of the bombers as planned. Zemke spotted German formations assembling at twenty-eight thousand, fifty miles ahead.

The P-47s dove—same tactics that had worked in October: high-speed attack, single pass, zoom-climb recovery.

But something was different.

The Luftwaffe had adapted.

German fighters no longer massed in one easy-to-spot block. They spread into small groups—four-aircraft sections that were hard to see and harder to catch all at once.

When the P-47s dove on one section, two more sections attacked from different angles.

The combat spilled across forty miles of sky.

The 56th couldn’t maintain cohesion while engaging multiple small units. The fight shattered into dozens of individual engagements. P-47 pilots found themselves alone, outnumbered, fighting multiple opponents at once.

Lieutenant Robert Johnson tangled with three Messerschmitt 109s over Brunswick. He destroyed one and damaged another. The third got on his tail.

Johnson dove.

The Messerschmitt followed.

Both aircraft accelerated past four-fifty.

Johnson pulled out at eight thousand feet. The German pilot blacked out under the G and crashed.

Across the battle space, the pattern repeated. German pilots tried to turn with the P-47s.

Physics killed them.

American pilots climbed away.

Mathematics saved them.

The Thunderbolt’s power-to-weight at combat speed exceeded anything the Luftwaffe could match.

The bomber stream reached Leipzig. German flak batteries opened up—88s, 105s. The sky filled with black bursts.

Twenty-one B-17s went down over the target.

Flak, not fighters.

The Luftwaffe never got through.

The 56th escorted the bombers back to England and landed at Halesworth in the late afternoon. Total mission time: six hours and forty minutes.

Eighteen German fighters confirmed destroyed.

Two P-47s lost.

Both pilots survived and evaded capture.

Big Week continued for five more days: Brunswick, Regensburg, Augsburg, Gotha, Schweinfurt again.

And then came the mission everyone said was impossible.

Berlin.

March 6th, 1944.

Before dawn at RAF Halesworth, Zemke briefed his pilots for the deepest-penetration mission ever attempted by American fighters—Berlin, five hundred and ten miles from the English coast.

The German capital had never been reached by escort fighters. Every previous Berlin raid had lost bombers by the dozen to unopposed Luftwaffe attacks.

The plan was ambitious.

Six hundred and sixty B-17s would hit industrial targets across the city. Three hundred and ninety-seven Fortresses targeted the VKF ball-bearing plant in Erkner. Two hundred and sixty-three struck the Daimler-Benz engine factory.

If the bombers survived, the raids would cripple German tank and aircraft production.

Eighth Air Force assigned eight fighter groups to escort duty.

Total: six hundred and seventy-three fighters.

Germany scrambled to defend Berlin. The capital had never fallen to daylight bombing.

It wouldn’t fall today.

The 56th crossed into Berlin airspace near midday.

The first American fighters over the city.

Zemke spotted German formations almost immediately—seventy-plus contacts at twenty-eight thousand, five miles ahead of the bomber stream. Focke-Wulf 190s and Messerschmitt 109s mixed together.

The Luftwaffe had committed everything.

The P-47s dove from thirty-three thousand.

Zemke led the first strike.

His flight hit at four-sixty.

The initial pass destroyed six fighters in eleven seconds. The German formation exploded outward, scattering across the sky.

Zemke’s wingmen followed through.

Three more Focke-Wulfs fell.

Above Berlin, the fight turned three-dimensional. P-47s dove from altitude. German fighters clawed upward toward the bombers. Both forces collided around twenty-five thousand. Tracers and cannon fire stitched the air. Debris fell toward the city.

Zemke destroyed a Focke-Wulf over the Dümmer Lake area—his second kill of the day. His wingman cut down a Messerschmitt.

The combat drifted west as the Germans tried to regroup.

The P-47s stayed with them: diving attacks, zoom climbs, no turning engagements.

What had worked in October worked over Berlin.

The bomber stream reached the target. Berlin’s flak defenses opened up—two thousand anti-aircraft guns. The sky went black with bursts.

Sixty-nine B-17s took damage.

Eleven went down.

But not one bomber fell to German fighters during the bomb run.

The escorts held the Luftwaffe away from the formations.

Half an hour later, the fighting ebbed. The bombers turned west. German fighters broke off.

Fuel exhaustion forced both sides to disengage.

The 56th formed up and headed home.

They landed back at Halesworth in the afternoon. Total mission time: six hours and ten minutes, the longest fighter mission flown by any American group to that date.

Intelligence tallied the results.

Eighteen German fighters confirmed destroyed over Berlin.

Four probables.

Nine damaged.

Two P-47s lost.

One pilot recovered.

One captured.

But the numbers only hinted at what mattered most.

American fighters had reached Berlin.

They had protected the bombers.

They had won the air battle over the German capital.

The mission every expert said was impossible had succeeded.

Zemke received the Distinguished Service Cross for leading the Berlin escort. The citation referenced his tactical innovations, his leadership under fire, his role in turning the P-47 from liability into one of Eighth Air Force’s most effective weapons.

Three months later, the 56th would do something even more remarkable.

May 1944.

Allied planners prepared Operation Overlord—the Normandy invasion. D-Day required absolute air superiority over the beaches. Luftwaffe fighters could not be allowed to reach the invasion fleet, strafe the sand, or disrupt airborne landings.

That mission fell to the fighter groups of Eighth Air Force.

The 56th moved to Boxted airfield in Essex, closer to the Channel, better positioned for round-trip missions to Normandy.

Their assignment was blunt: sweep ahead of the bombers, destroy German fighters before they reached the invasion zones, maintain constant patrols over the water.

From May 8th through June 5th, the group flew thirty-two missions in twenty-nine days—fighter sweeps, bomber escort, armed reconnaissance, ground attack.

The tempo exceeded anything from 1943. Pilots flew six days per week, sometimes twice per day.

Everyone was exhausted.

Everyone kept flying.

June 6th.

D-Day.

Before first light, the 56th launched. First wave: fifty-one P-47s swept the French coast ahead of the invasion fleet.

Their mission was simple: destroy any German aircraft attempting to reach the beaches.

Not one Luftwaffe fighter would get through.

At dawn over Normandy, the sky was empty.

The Luftwaffe had pulled back from coastal airfields days earlier. Allied intelligence knew they were holding inland for counterattacks.

If the Germans wouldn’t come to them, the Americans would go to the Germans.

After sunrise, Zemke spotted aircraft lifting off from an airfield near IU—Focke-Wulf 190s scrambling to meet the invasion.

The P-47s attacked during the takeoff sequence, when fighters were most vulnerable: heavy, slow, pinned to a runway, unable to maneuver.

Nine Focke-Wulfs were destroyed on the ground.

Four more were shot down in the climb.

The rest aborted and scattered.

Not one reached the beaches.

The 56th returned to Boxted in the morning, refueled, rearmed, and launched again late morning.

Second mission of D-Day: armed reconnaissance over the Falaise area.

They intercepted German fighter-bombers trying to reach Allied positions—Junkers 88s, Focke-Wulf 190s carrying bombs, Messerschmitt 110 night fighters pressed into daylight.

The Luftwaffe was throwing everything it had at the invasion.

By sunset, the 56th had flown ninety-seven individual sorties.

They claimed twenty-three German aircraft destroyed—fifteen on the ground, eight in the air.

Zero American losses.

The invasion succeeded in part because German fighters never reached the beaches in significant numbers.

But June 6th was one day.

The campaign dragged through June, July, and August. The 56th flew constant missions supporting the breakout—strafing convoys, wrecking fuel depots, hammering rail yards.

The P-47’s eight .50-caliber guns proved devastating against ground targets. Armor-piercing incendiary rounds punched through truck engines, fuel tanks, and locomotives.

In August 1944, Zemke received orders to transfer to the 479th Fighter Group, a struggling unit equipped with P-38 Lightnings and converting to P-51 Mustangs. Eighth Air Force needed him to rebuild them.

His time with the 56th was over.

Lieutenant Colonel David Schilling assumed command. Schilling had been with the group since early 1943. He understood Zemke’s system completely.

The transition was seamless.

The group’s performance never declined.

Under Schilling, the 56th continued operations through the end of 1944 and into 1945: the Battle of the Bulge, the push to the Rhine, the final drive into Germany.

The group flew its last combat mission on April 21st, 1945—eighteen days before Germany surrendered.

When the Air Force Historical Research Agency compiled the numbers, the record was undeniable.

Two years of combat operations.

Four hundred and forty-seven missions flown.

Nineteen thousand three hundred and ninety-one sorties.

Sixty-four thousand three hundred and twenty hours of combat flight time.

Six hundred and seventy-seven and one-half German aircraft destroyed in air-to-air combat—the highest total of any fighter group in Eighth Air Force.

One hundred more victories than the second-place unit.

The only fighter group in the European theater that flew the same aircraft type from first mission to last.

The P-47 Thunderbolt the Germans had mocked as too heavy for combat destroyed more Luftwaffe fighters than any other American aircraft.

Not because the airframe changed.

Because the tactics changed.

Zemke’s diving attacks. His altitude discipline. His refusal to dogfight. His mathematical approach to aerial combat.

These innovations transformed the strategic bombing campaign. They made D-Day possible. They won the air war over Europe.

And it started with one realization.

The P-47 couldn’t turn.

So stop trying to make it turn.

Zemke transferred to the 479th Fighter Group in August 1944. His new unit flew P-51 Mustangs.

Different aircraft.

Same principles: height advantage, diving attacks, speed over maneuverability.

He scored two and one-half additional victories with the 479th, bringing his total to seventeen and three-quarters confirmed kills.

In late October 1944, Zemke led a mission over Germany in deteriorating weather and severe turbulence. His P-51’s wings separated at eighteen thousand feet.

He bailed out.

He evaded for three days.

German troops captured him in early November.

He spent the remainder of the war in Stalag Luft I as the senior Allied officer, responsible for nine thousand prisoners.

But the 56th didn’t need Zemke anymore.

His tactics had become doctrine. Every pilot understood the mathematics. Every new replacement learned the system.

The success continued under Schilling through the final seven months of the war.

The group produced thirty-nine fighter aces, more than any other Eighth Air Force unit.

Lieutenant Colonel Francis Gabreski scored twenty-eight victories with the 56th—the highest total of any American pilot in the European theater.

Captain Robert Johnson finished with twenty-seven.

Colonel David Schilling claimed twenty-two and one-half.

Major Walker Mahurin reached twenty and three-quarters.

These weren’t lucky pilots.

They were disciplined tacticians who understood physics.

They knew their aircraft’s capabilities.

They refused to fight the enemy’s fight.

They made the Luftwaffe fight theirs.

And the Luftwaffe lost.

By April 1945, other P-47 groups across Eighth Air Force had adopted variations of Zemke’s method: the 78th, the 352nd, the 353rd.

Combined, P-47 groups destroyed more than two thousand German aircraft in air-to-air combat.

The supposedly obsolete fighter became the most successful American aircraft in the European theater.

The strategic bombing campaign succeeded because fighters like the P-47 made it succeed.

Bomber losses fell from twenty percent per mission in 1943 to less than two percent by 1945.

German industrial production collapsed—ball-bearing plants, aircraft factories, oil refineries, tank works—pounded by bombers protected by escorts that finally worked.

Zemke survived the war, returned to the United States in 1945, and remained in the Air Force until 1966, retiring as a full colonel. He never received a general’s star despite leading one of the most successful fighter groups in American history.

Some said his outspoken criticism of senior officers cost him promotion. Others said the Air Force preferred leaders who didn’t question doctrine.

Either way, Zemke changed warfare regardless of rank.

His mathematical approach to aerial combat influenced fighter tactics for decades. Vietnam-era F-4 Phantom crews used energy-management ideas traced straight back to the P-47 doctrine: height advantage, speed advantage, boom-and-zoom.

The principles held even as speeds doubled and tripled.

The 56th Fighter Group disbanded in late 1945, reformed the next year, and served through the Cold War—flying F-86 Sabres in air defense, converting to F-100 Super Sabres, then F-4 Phantoms.

Today the unit trains F-16 pilots at Luke Air Force Base in Arizona.

The Wolfpack continues.

If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor: share it with someone who loves history, or leave a comment below. Every share helps these stories reach more readers, and every comment helps keep the archive alive.

We’re rescuing forgotten stories from dusty records every single day—stories about pilots and commanders who saved lives with tactics, mathematics, and discipline.

Real people.

Real heroism.

If you’d like, tell us where you’re reading from. United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia—our community stretches across the entire world. You’re not just a reader. You’re part of keeping these memories alive.

Tell us your location.

Tell us if someone in your family served.

Just let us know you’re here.

Thank you for reading, and thank you for making sure Hubert Zemke and the 56th Fighter Group don’t disappear into silence.

These men deserve to be remembered—and you’re helping make that happen.

Note: This is a historically grounded, dramatized narrative about World War II air combat, written for educational purposes. It contains references to wartime violence but avoids graphic detail.

News

November 2nd, 1944. 3:47 p.m., somewhere over Czechoslovakia—and Lieutenant Bruce Carr watches the oil pressure needle fall to nothing as black smoke curls past the canopy of his P-51 Mustang.

November 2nd, 1944. 3:47 p.m. Somewhere over Czechoslovakia, Lieutenant Bruce Carr watches the oil pressure gauge drop to zero. Black…

One pilot in a p-40 named “lulu bell” versus sixty-four enemy aircraft—december 13, 1943, over assam.

At 9:27 a.m. on December 13th, 1943, Second Lieutenant Philip Adair pulled his Curtiss P-40N Warhawk into a climbing turn…

0900, Feb 26, 1945—on the western slope of Hill 382 on Iwo Jima, PFC Douglas Jacobson, 19, watches the bazooka team drop under a Japanese 20 mm gun that has his company pinned. In black volcanic ash, he grabs the launcher built for two men, slings a bag of rockets, and sprints across open ground with nowhere to hide. He gets one rise, one aim—then the whole battle holds its breath.

This is a historical account of the Battle of Iwo Jima (World War II), told in narrative form and intentionally…

THE DAY A U.S. BATTLESHIP FIRED BEYOND THE HORIZON — February 17, 1944. Truk Lagoon is choking under smoke and heat, and the Pacific looks almost calm from a distance—until you realize how many ships are burning behind that haze.

February 17, 1944. The lagoon at Truk burns under a tropical sky turned black with smoke. On the bridge of…

A B-17 named Mispa went over Budapest—then the sky took the cockpit and left the crew a choice no one trains for

On the morning of July 14, 1944, First Lieutenant Evald Swanson sat in the cockpit of a B-17G Flying Fortress…

Papy Gunn’s “Impossible” Gunship — In the early hours of World War II’s Pacific fight, at 7:42 a.m. on August 17, 1942, Captain Paul “Papy” Gunn crouched under the wing of a battered Douglas A-20 Havoc at Eagle Farm outside Brisbane, watching mechanics weld .50-caliber machine guns into the bomber’s nose—right where the bombardier used to sit.

On the morning of August 17th, 1942, Captain Paul Gun crouched under the wing of a Douglas A-20 Havoc at…

End of content

No more pages to load